Duigan on Colin OAM

Sometimes works of art linger in the imagination long after departing from the gallery, as happened for Jan Duigan on viewing two remarkable works by Tjikalyi Colin, OAM (1942 – 2002), currently on view in the Higgins Gallery. Here Duigan shares her interest and research, beginning with her misgivings about the frames.

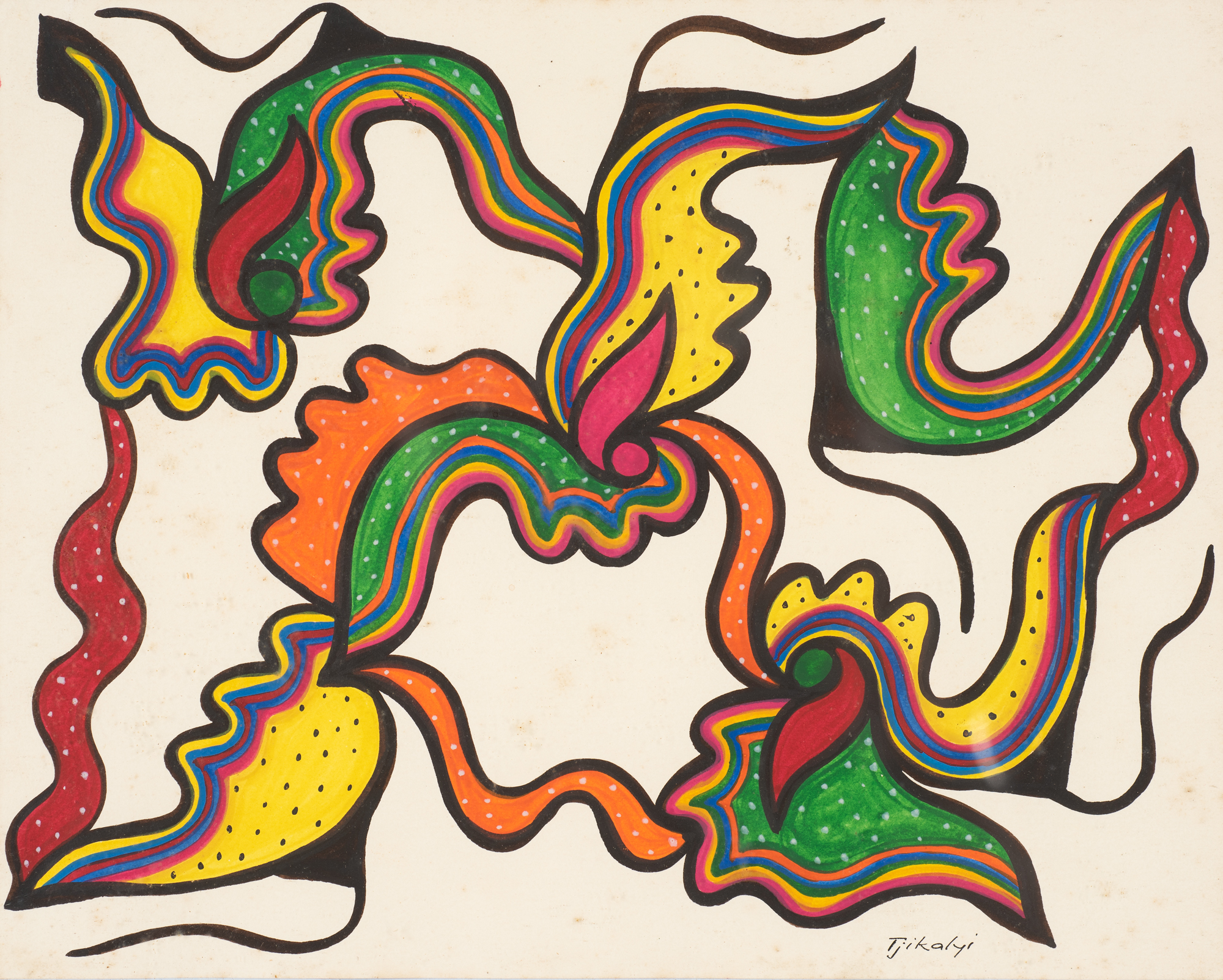

CAM’s recent exhibition Melinda Harper: In Conversation with the Collection has been the catalyst for conversations that go well beyond the interaction of her artworks with selections from the CAM collection. Two works selected by Harper have caught my attention, these are two walka paintings by Tjikalyi Colin. These are Ernabella paintings, done by Pitjantjatjara women in the early days of the Ernabella Mission in remote South Australia. Such paintings are rarely seen in art galleries or mounted and framed as those exhibited here.

After leaving Melinda’s exhibition, I could not dismiss these little works from my thoughts. They have an elusive quality that tantalises and beckons the viewer into a world beyond our imagination. How did they come to be in the Castlemaine collection? And what about the inappropriate framing?

I followed my curiosity, drawn into Melinda Harper’s conversation. As did Kevin Murray, who in an earlier Reflection introduced us to the artist, the origins of the walka motifs, the donors of the paintings (Rev. and Mrs Alec Hilliard) and their relationship with the mission.

As with all art, the walka paintings reflect their time and place. They speak to us of the long gone world of Pitjantjatjara girls and women at Ernabella Mission when they created these designs in the craft room as decorative motifs for an evolving art and craft industry. Traditional art involved the use of naturally occurring materials such as sand, sticks, ochre and charcoal. We can see the imaginative freedom that came to the artists with the arrival of water-based paints and brushes. They could paint their walka motifs using bright colours, bold shapes and flowing brush strokes on white paper. We also see the influence of the mission teachers and advisors in Tjikalyi’s signature — her given name, written in Western style.

Much has been written about walka — their origins, design and significance — but they remain enigmatic. To eyes tuned to the conventions and stylistic imagery of Western art, the underlying concept of Tjikalyi Colin’s paintings is not obvious. They are untitled. The abstraction appears without context. Anthropologists and ethnographers have suggested that the walka paintings of Ernabella are deliberately obscure in meaning. The artists did not want to share details of their Tjukurpa (sacred knowledge, songlines or Dreamings) with outsiders. Moreover, the paintings do not have the iconography that we find in other Indigenous art, such as the Papunya Tula paintings of the Western Desert.

Times have changed since Tjikalyi painted her walka. The missions withdrew from Indigenous lands, the Ernabella craft room transitioned to become Ernabella Arts Inc, and its artists’ output has broadened so that the early walka designs no longer predominate. The Ernabella artists now look to their Tjukurpa as the sources of much of their art. There is an increasing ease and exchange of ideas. This was clearly seen in the Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters exhibition at the National Museum of Australia, Canberra, in 2017, which included the art and culture of the Anangu, Pitjantjatjara, Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands through which the songlines pass, Tjikalyi’s country.

So how do these paintings come to be exhibited in those inappropriate frames? Made of white painted timber moulding with a narrow, pale-blue mat, the small frames confine the paintings within a very tight space. They bear no apparent relationship to the subject. They are of a style that was popular in domestic decor around the time the works were gifted to CAM, we assume they were given already framed. The donors, the Reverend Alec and Mrs Ruth Hilliard, lived in Castlemaine, where Alec was the Presbyterian Minister from 1957 to 1966. The Hilliards had very close links with the Ernabella Mission, starting from Ruth’s time there as a nurse in 1949 and 1950. Alec’s sister, Deaconess Winifred Hilliard, was even more closely involved, having lived and worked for more than 30 years among the Pitjantjatjara people.

It was inevitable that the Hilliards would collect pieces from Ernabella. Winifred Hilliard donated much of her large collection to the National Museum of Australia in Canberra. Alec and Ruth gave many items to friends and family during their lifetimes. Their gift of the two walka paintings to CAM is entirely in character. The paintings were most likely framed for the Hilliards in the late 1950s or early 1960s.

My misgivings about the frames are wavering. Knowing the journey these small paintings have taken to hang on the CAM gallery walls, I can now see the frames as an integral part of that journey. I wonder if others agree?

Jan Duigan

September 2021