Murray on Colin OAM

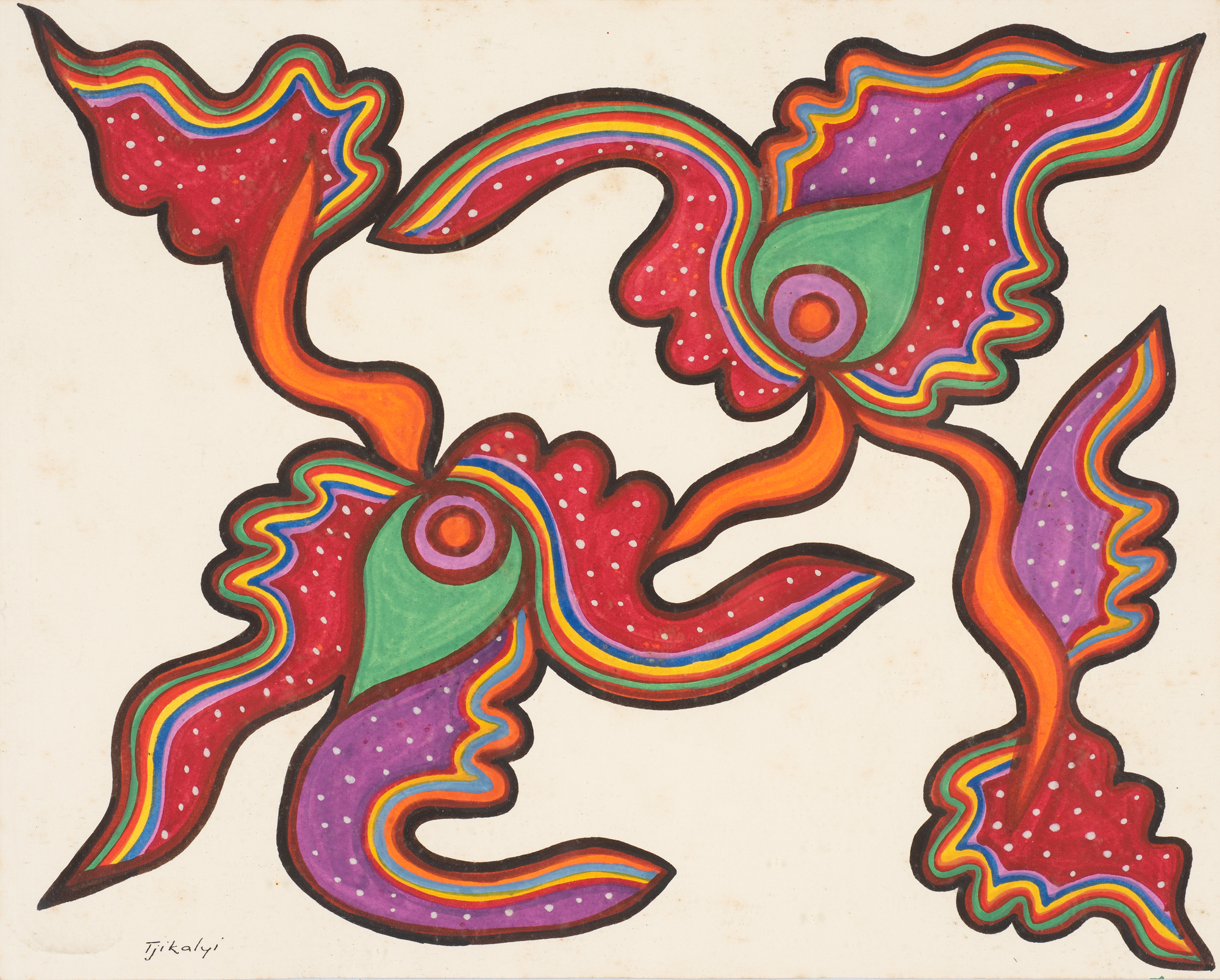

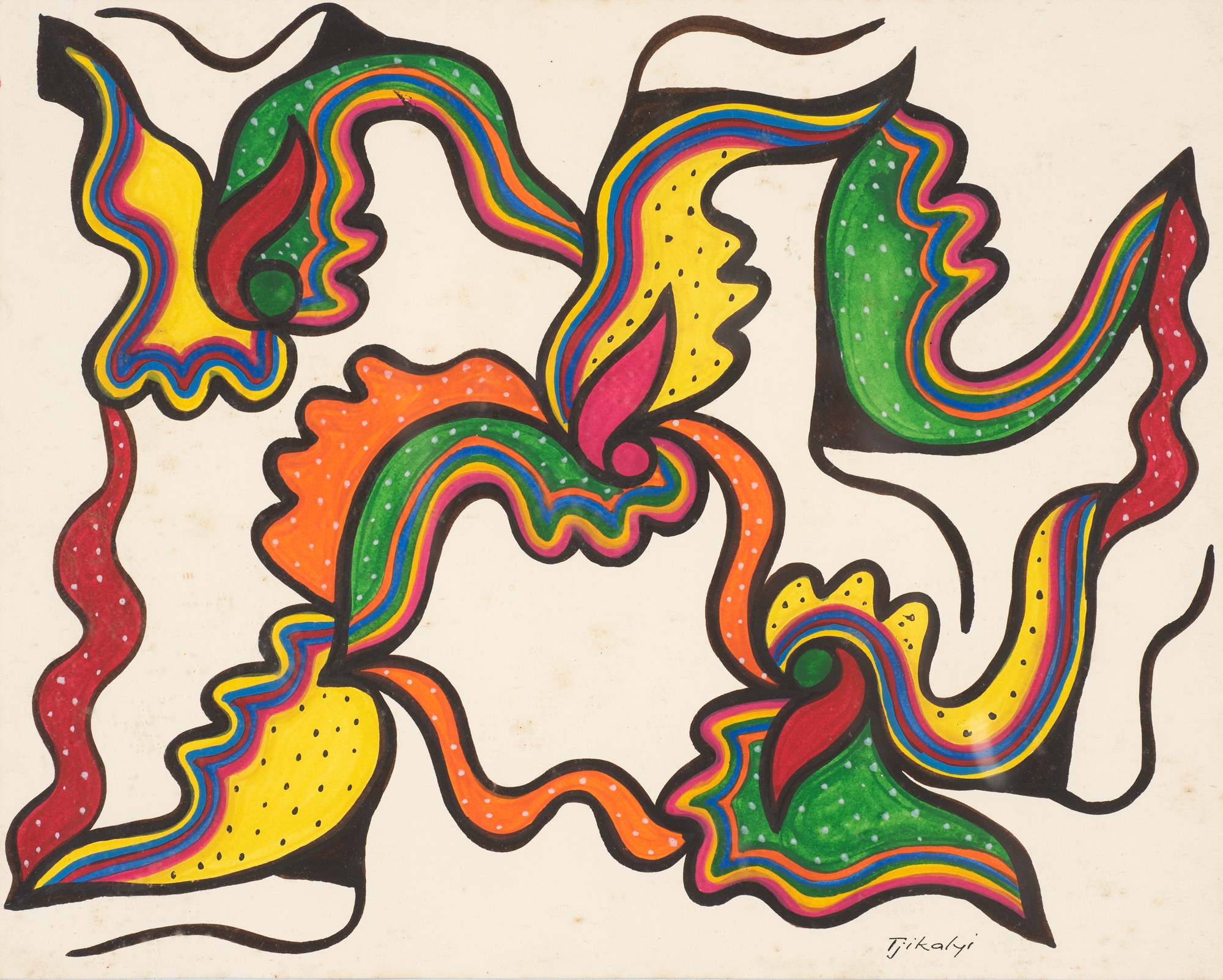

Melinda Harper selected two remarkable watercolours by First Nations artist, Tjikalyi Colin, OAM (1942 – 2002) for her In Conversation exhibition currently showing in the Higgins Gallery. Not only do they resonate with Harper's works on paper, but they are a welcome and curious addition to the collection. CAM's records are slender on these works, except for the name of artist and donor. However, interest in the works is such that members of the community have stepped forward with comments and background on Tjikalyi Colin. Here writer Kevin Murray reflects on what we now know about the artist, the local donor and the donor's relationship with Ernabella, South Australia.

These two vibrant works on paper seem a world away from sober Castlemaine, but their story is intertwined with the town’s history. In 1961, the grand Presbyterian Church that stands opposite CAM celebrated its centenary. The Reverend Alec Hilliard OAM (d. 2020) gifted the two artworks, which had been obtained by his sister, Winifred, then working in a Presbyterian mission in Central Australia. Alec’s wife Ruth (dec.) had worked at Ernabella Mission as Nursing Sister Ruth Dawkins 1949-50, some two years prior to their marriage.

Located 330k south-west of Alice Springs, Ernabella has a relatively high elevation which makes it suitable for sheep grazing. In 1937, the pastoral station was taken over by the Scottish missionary, Dr Charles Duguid, as a buffer against encroaching white settlers. He insisted the new mission respect local language and culture. And so children were never separated from parents, as happened elsewhere at the time.

Winifred Hilliard was inspired by an aunt who became a missionary in Korea. She took the opportunity to join Ernabella mission in 1954 as a craft advisor. She ended up staying for 32 years, and eventually took on the Pitjantjatjara name “Awularinya”. Her time is now known as “Hilliard time”, like the mythical “Thomson time” that evokes the stay of anthropologist Douglas Thomson in the film Ten Canoes.

In Hilliard’s book, The People In Between: The Pitjantjatjara People Of Ernabella, she described how walka emerged. In 1940, the mission’s teacher and soon to be superintendent, Rev. Ron Trudinger, was trying to encourage pupils to be creative and make “free” crayon drawings on paper in the classroom. But the students seemed inhibited and reluctant to express themselves in the absence of clear instructions. Eventually, Trudinger asked them to take up their crayons and, not yet fluent in the Pitjantjatjara language, used the mistaken “kura kura walka tjunkupai”, meaning "to draw not much good" (kura kura) instead of “anything” This gave them a license to make art free of any anxieties about what was proper image-making in the context of cultural restrictions relating to sacred designs. The result was a free creative style that may appear like doodling but has serious formal qualities.

Despite its improvised quality, walka is rich in associations, including body paintings and “natural” patterns such as spider's web, spiral snail shells and flowers. In the wider context of Central Australian painting at the time, walka became very much a girl's and women’s art, in contrast to the expression of men’s cultural power in the more prominent Papunya Tula painting movement.

Building on this creative confidence, Hilliard encouraged the use of these designs in a variety of products, such as hand-tufted rugs, burlap wall hangings, kangaroo skin moccasins, silk scarves and table cloths.

By the 1970s, walka began to have an international profile. In 1973, the mission was handed over to the community and Ernabella became known as Pukatja. At that time, with encouragement from Mary White, craft adviser for the Australia Council, they began an exchange with Yogyakarta to learn batik, a medium that complemented the fluid nature of walka designs. This led to visits to the National Museum of Ethnography in Osaka, Japan, in 1983.

For anthropologist Ute Eickelkamp, walka need to be understood as a repetitive process, like sand storytelling. As with the construction of a mandala, the process has value in addition to the final design. Part of the process is the alternation between outline and infill. As she quotes the late artist, Tjikalyi Colin, "We make lines, follow this direction, then I look and go the other way". There are also layers of meaning about the kinship system that are relevant to the Anangu.

It was Tjikalyi Colin who created the two works that are in the CAM collection. They were acquired in 1961, so made when she was 19 years or younger. Tjikalyi became a significant figure in Ernabella and the regional Indigenous Women’s Council in Alice Springs, where she inspired the development of Mai Wiru, a “healthy food" project. For this and other contributions to her community, she received an OAM In 1994.

Walka continues to be a source of creativity today. Besides textiles, walka has been applied to other art forms such as punu wood sculptures and terracotta ceramics.

While it might seem Puritan in disposition, the Presbyterian church does help nurture an art that can fill the gallery opposite. The Bible tells us that “Good and upright is the LORD” (Psalm 25:8), but something splendid can arise when we stray from the orthodox path.

Kevin Murray

August 2021

References

Eickelkamp, U. (ed) (1999). Don’t Ask For Stories; The Women from Ernabella and Their Art. Aboriginal Studies Press

Eickelkamp, U. (2005). 'We make lines, follow this direction, then I look and go the other way'. Excerpts from an ethnography of the aesthetic imagination of the Pitjantjatjara. In T. Heyd, & J. Clegg (Eds.), Rock Art and Aesthetics (pp. 143-158). Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Hilliard, Winifred The People In Between: The Pitjantjatjara People Of Ernabella Adelaide: Rigby, 1976

“Ernabella Letters - Extracts of Letters written from “Ernabella” in the Musgrove Ranges, South Australia 1949-50”. Privately published by Alec and Ruth Hilliard in 1994.

Partos, Louise (ed.), 1998 A Celebration of 50 years of Ernabella Arts. Ernabella Arts Inc.

Pybus, Carol Ann. “We grew up in this place”: Ernabella Mission 1937-1974. Ph.D. Submission, University of Tasmania 2012.

Young, D. J. B. (2017) ‘Deaconess Winifred Hilliard and the cultural brokerage of the Ernabella craft room’, Aboriginal history, 41, pp. 71–94.

Thanks to Ute Eickelkamp and Janette Duigan for their help with this reflection.