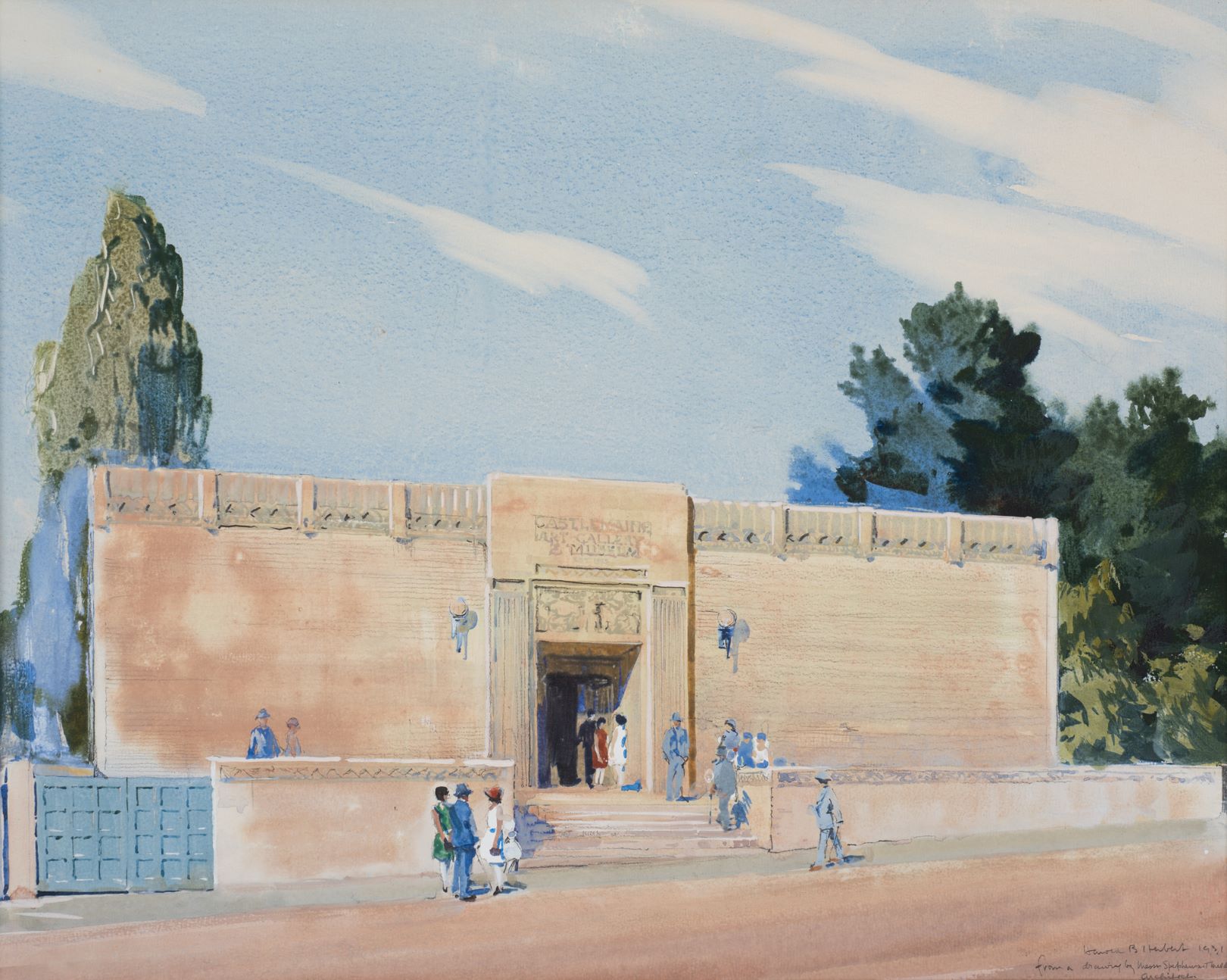

Tindal on the CAM Façade

Dr Evan Tindal, Principal Objects Conservator with the Grimwade Conservation Service at the University of Melbourne, was invited to assess damage to the museum's façade. Here, Dr Tindal sheds some light on the issues he addressed on first inspecting the building.

Dr Evan Tindal on the Castlemaine Art Museum Façade

When invited to assess the Art Deco façade gracing the front of the gallery I found myself face to façade with an intricate intersection of human and natural influences. Our objective as art conservators when visiting a site is to first evaluate the condition of heritage material in that moment. We want to take a snapshot of a period in time, around which to compare previous assessments and identify any changes that may occur in the future. Importantly, the object’s condition also informs recommendations for remedial works necessary to stabilise deterioration.

All materials are susceptible to deterioration, some more so than others, and even those we might perceive to be impenetrable. Scanning the surface of the façade triggered in me a curiosity about how these materials have interacted with the natural environment, and how this may be affecting both the structural condition and aesthetic experience of the work. Painting an austere backdrop against which it might be difficult to imagine Mother Nature impacting such robust materials, on closer inspection the evidence of these mechanisms is present. The culprit? …that little ole sustainer of life: water. Peppered throughout, and often running vertically from top to bottom, we can see direct evidence of its influences on the façade.

In the first instance, white streaks can be viewed originating from several joins between the tiles, especially around the “Est. 1913” dedication. These take the shape of water lines, providing some insight into the cause. But what is responsible for the white precipitate that remains when the water evaporates and why are only small areas impacted? That the white streaks originate at a join between two tiles tells me that this substance likely comes from here. What joins two tiles? Lime mortar. Comprised primarily of calcium-containing minerals, the white streaks stemming from these joins likely result from water-soluble calcium carbonates present in the lime mortar. As rain water flows over and into these recessed joins, it dissolves calcium into solution, which is subsequently deposited onto the face of the tiles as the water flows downwards—not at all dissimilar to the scale building up one might find in their kettle in areas with hard, mineral-rich water.

A dingy soiling-of-sorts is also visible on the façade, presenting a stark contrast to the white calcium carbonate precipitate. Again, while seemingly random in their positioning on first glance, the presence of these dark spots also follow a specific pattern. One might be tempted to assume that the culprit lies with dirt or pollution. However, shadowing small cracks and recessed grooves, these dark areas are concentrated in areas where water can congregate. Water promotes biogrowth, which appears on surfaces like these as dark clouds of lichen and other biological organisms. As the adage goes, “Life finds a way!”

These details tell a story of art within the world: of built heritage and time passing. They are testament to a million little forces combining to create what we see with a moment’s glance upwards. While these changes can sometimes be perceived as wholly negative, there is value in the random processes that have made the façade what it is today. We take note of them. We photograph them. And we consider their impacts. Sometimes interventions are necessary to slow these processes and prolong the life of the object. The natural environment is a harsh one, toppling mountains to the sea if given the time. Through conservation works, these forces are stymied and the hand of the conservator becomes yet another story added to the long list of others influencing this work.