Soumilas on a mourning cape

In reflecting on a costume in our collection Annette Soumilas, explores the social history and meaning of this striking black cape.

Black clothing became the official signifier for death and mourning in nineteenth century Britain. Women were obliged to dress in black from head to toe when grieving a loved one for extended periods of time. The cult of mourning took an obsessive hold during Queen Victoria’s reign following the death of Prince Albert in 1861. Victoria’s attire set the dress code which was strictly adhered to by those who could afford to do so and eventually extended to all social classes. This mania did not wane until after Queen Victoria’s own death in 1901. Today black endures as the dress code for official mourning.

CAM’s collection of historic dress includes a mourning cape from the late 1890’s, donated by a David Dunstan (date of donation unknown). The three-quarter hip length women’s cape was manufactured in Britain from dull silk bombazine, it is lined with silk and interfaced with stiffened cotton netting and has a modest trimming of crape frill on the collar and shoulders.

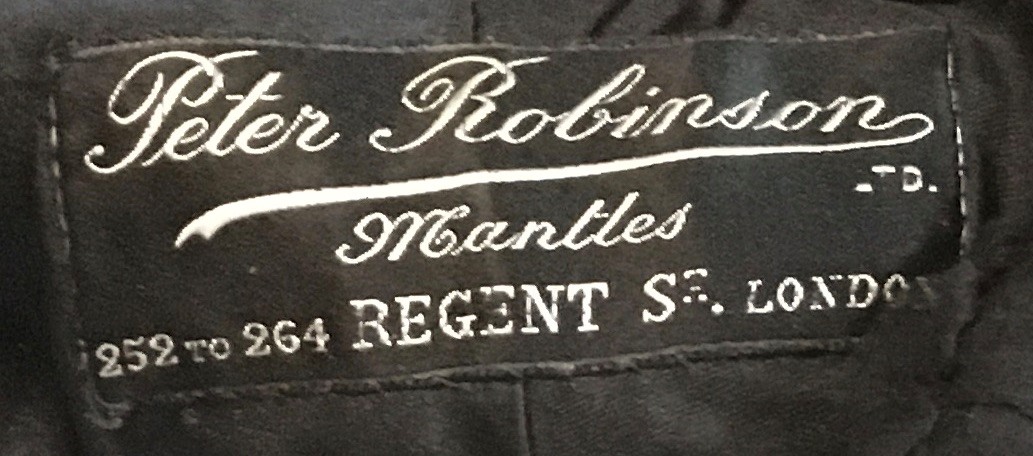

Detail of label. Peter Robinson Ltd, Ladies opera cape, 1870s. Castlemaine Art Museum, donated by David Dunstan. Image: Annette Soumilas.

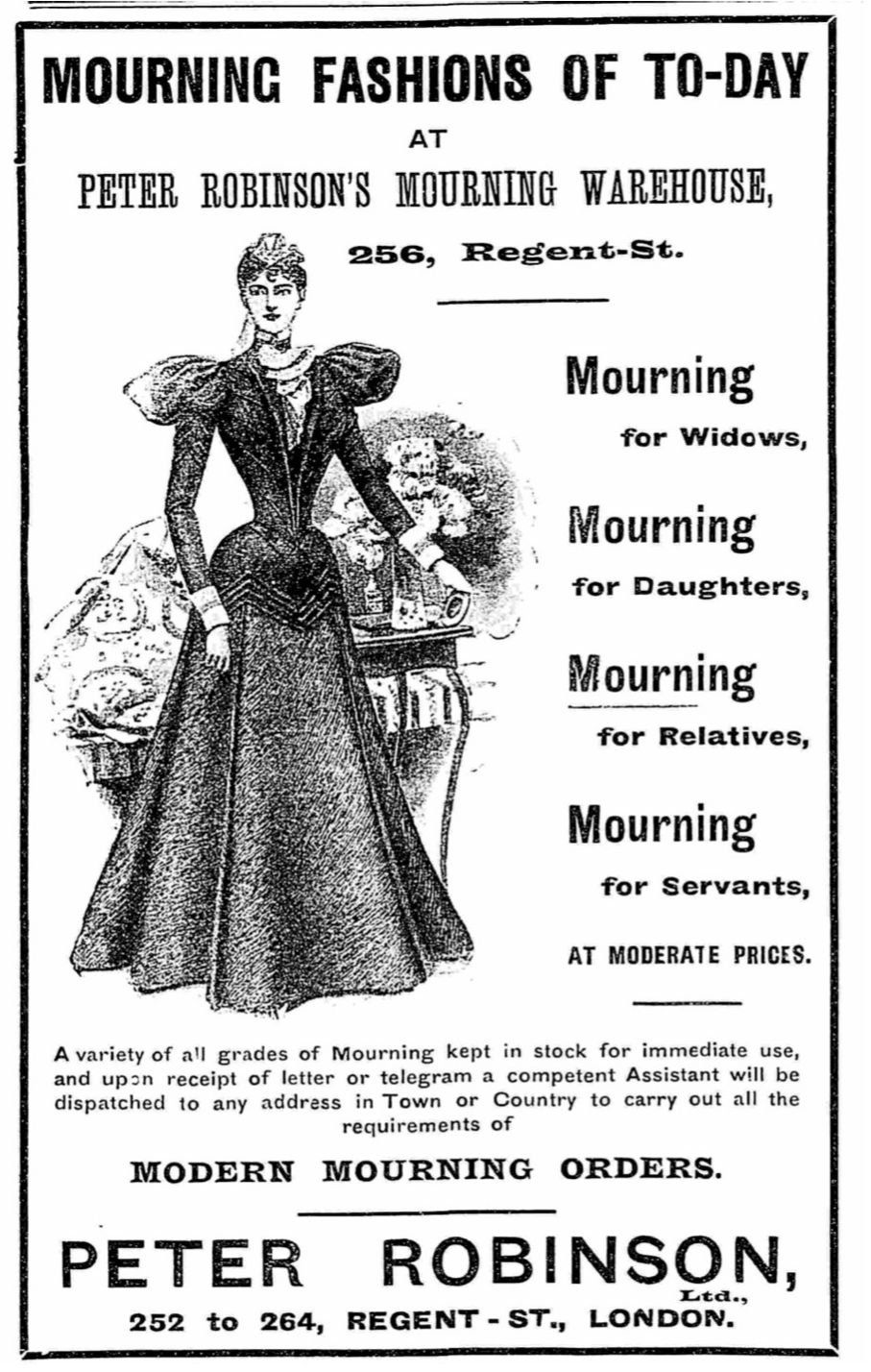

The cape is labelled, Peter Robinson Ltd, 252 to 264 Regent Street London. Its styling, colour and cloth are typical of ready-made mantles manufactured at this time. Mourning warehouses such as Peter Robinson’s and his rival Jay’s retailed every conceivable good associated with the theatre of death. This was a lucrative and competitive business.

Nineteenth century Australians either strictly observed British mourning traditions as dictated by British and local newspapers and fashion periodicals, or adapted the rules according to religion, social rank and economic status. Mourning clothing was either homemade, made to order by a dressmaker or purchased at an emporium or draper.

As in Britain, department stores and drapers specialising in mourning clothes were established in Australian cities and towns. Melbourne newspapers such as The Argus and The Age frequently advertised mourning attire either imported or locally manufactured.

During the gold rush Castlemaine’s market square become a hub for smaller scale department stores and drapers. Late nineteenth century advertisements in the Mount Alexander Mail feature stock of the latest mantles, dresses and trimmings, available at McCreery & Hopkins, T. Brock & Co, Ball and Welch and Rylands. It is possible that these establishments imported Peter Robinson mantles.

Hearth and Home, vol. 13, no. [329], 2 September 1897, p. 646.

Widows not wishing to be shunned by society adhered to strict rules covering three stages lasting two and a half years in total. Deep mourning lasted one year and one day. A woman was obliged to dress in austere solid black attire from head to toe made from scratchy woollen cloth and crape. The drabber the better. Secondary or ordinary mourning permitted less crape and embellishments such as black jet. Purples, whites and grey were permitted during the final stage of mourning, lasting six months. Men, on the other hand, once the funeral was over, were only obliged to wear a black armband.

Voices of dissent against “widow’s weeds”, began to emerge with dress reforms as early as 1870 in Britain and consequently in Australia. By the close of the nineteenth century articles in local newspapers questioned the prohibitive cost of mourning dress but also the negative psychological effects resulting from wearing depressing black clothing for extended periods of time. In 1874, the author of the Sydney Morning Herald’s Opinion column stated: “A reformation in ladies’ mourning is greatly needed, for the present practice of wearing an entire suit of black on the death of a relation is to ladies of small means a most serious expense; and, as economical as well as suitable dress is a subject in which all ladies are interested, I hope you will help us to find some better way of showing our grief for the departed than by the blackness of our clothes.” (Sydney Morning Herald, 17 January 1874, p.98)

An article in the Bendigo Advertiser in 1887 describing the funeral of the late Rev. Henry Ward Beecher commented “not a bit of crape was to be seen… Does anyone believe that Mrs. Beecher, sitting beside the corpse of her husband in ordinary clothing whilst the funeral service was read, did not feel her great loss as keenly as if she had been draped in raiment of the deepest gloom?” (Bendigo Advertiser, 16 April 1887, p.2)

Mount Alexander Mail, Tuesday 2 June 1896, p. 3.

CAM’s cape has survived despite the prevailing superstition that it was unlucky to keep mourning clothes and probably because by the time the cape was purchased, attitudes toward mourning dress had changed. An article appearing in the Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times in 1899, states: “The custom of wearing mourning is now admittedly a very elastic one. Fashion has veered round completely on the question of the customary suit of solemn black to be assumed on the death of a relative.” (North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, Friday 31 March 1899, p. 1.)

By then, mourning clothes were styled to closely follow fashions of the day, and black had become fashionable for evening dress. Financial constraints caused many to repurpose mourning clothes, even dragging them out of storage to wear at a later date, despite “bad luck”. It is thus possible that the Dunstan cape was worn in 1901 when Britain and the colonies were mourning Queen Victoria’s death. An Australian woman upholding mourning dress codes at this time most likely did so to reflect both her social standing and her relationship to the deceased.

Annette Soumilas

April 2021

The fascinating history of royal family dress codes

Taylor Lou, Mourning Dress: a costume and social history, London; Boston: G. Allen and Unwin 1983.

Jalland, Patricia, Death in the Victorian family, Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press 1996.

Jalland, Patricia. Australian Ways of Death: a social and cultural history, 1840-1918, Melbourne; New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Australian etiquette Melbourne: People’s Publishing Co., 1886.

Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion, Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific Islands, eBook, Maynard M, ed, Eluwawalage D, Settler Dress in Australia, pp. 81-85.