Siggins on Brack

John Brack’s Surrey Hills floats high on a blue wall in Melinda Harper’s current exhibition at CAM, adding to its curious perspective and abstraction. No stranger to CAM Reflections, here Phillip Siggins discusses one of the collection highlights.

John Brack is an artist who casts a humorous, jaundiced, sometimes affectionate, eye over Australian life. This painting, Surrey Hills, is as sarcastic a comment on a dry suburb (no pubs allowed) as anything uttered by Dame Edna Everage as she ripped into the lives of those sheltering in the post war Melbourne suburbs. Her gimlet eye fell particularly on Camberwell, home of Sandy Stone, the ultimate suburban male of 1955 who, reincarnated in pyjamas in his armchair in the Camberwell op shop delivered a monologue of searing pathos and banality about the tiny dramas of his oppressed, former life. Have you seen Brack’s portrait of a multi-coloured Dame Edna at the Gallery of NSW? She leans into the picture resplendent in her hat, gloves, edge to edge coat and costume, ready to draw blood and you into her gleeful, twisted world. You’ll die laughing but be afraid, be very afraid!

John Brack started painting seriously in the late 1940s, after his return from the war. Like so many returned soldiers he was for the rights of workers and for equality of opportunity. Like so many of his repatriated peers he was impatient with and critical of outmoded institutions and ways of thought.

His most well known painting is Collins Street, 5p.m. (1955) and it has been described as ‘the only existential painting to be produced in Australia’ It illustrates the drudgery of nine to five office work, and gives visual expression to the belief that modern life was characterised by alienation, boredom and a sense of disorientation that emerges in the face of an apparently meaningless and absurd world. Brack acknowledged that Collins Street, 5pm made reference to T. S. Eliot’s The Waste land, specifically the passage from ‘The burial of the dead’:

Unreal City,

Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,

A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many

I had not thought that death had undone so many¹

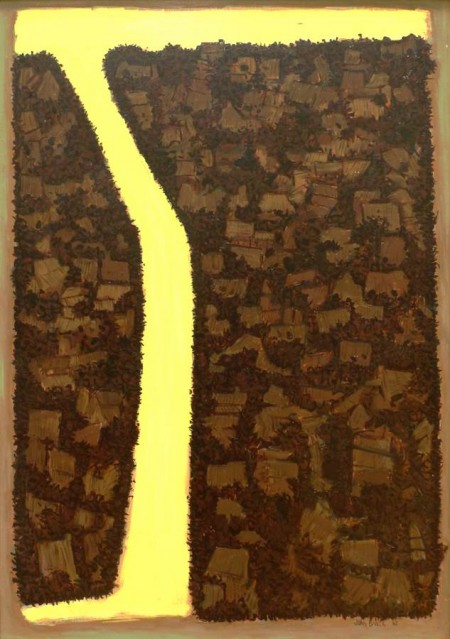

This sense of alienation/repudiation is also found in Surrey Hills. At first it is a little difficult to work out what we are looking at. The viewpoint is high up and there is no horizon. Below us a brown/black surface is bisected by acid yellow strips. Is this a painting of country by a first nation’s artist? Or is it an early landscape by Fred Williams?

But on closer inspection we see that the curious black lines and marks upon the brown surface are describing the roofs of huddled little houses and the acid yellow strips are roads. Brack has succeeded in evoking an unpleasant sense of a suppressed, deeply conformist suburb. The yellow roads don’t unite but cut up the canvas, suggesting a landscape divided against itself. If there is any pity in the painting it is in the sense that in so huddling together the inhabitants of Surrey Hills live lives of humility, if not of quiet desperation.

Nothing could be of greater contrast to the Australian Impressionist paintings in the gallery. These earlier landscapes of an idealized rural Australia, expressing new found patriotic pride and the promise of coming greatness, have been harshly repudiated by Brack’s response to the suburban landscape. In Surrey Hills little boxes made of ticky tacky sweep across the landscape promising boredom and puritanical conformity. And sorrow for dingy, constrained and unfulfilled lives. Surry Hills is now an uber expensive leafy suburb with a multi- cultural population, elegant shops, pubs and restaurants, but John Brack conveys a very different reality witnessed in 1962.

Phillip Siggins

February 2021