Siggins on Ramsay

In art as in life, hands can tell us something of an individual's age and possibly of their station in life. In this reflection on a portrait by Hugh Ramsay, Phillip Siggins shares with us the reaction of the portrait's famous commissioner, donor, and daughter of the sitter, Dame Nelly Melba to the artist's depiction of her father's hands. In 2019 Ramsay's portrait of David Mitchell was lent to the National Gallery of Australia for their major Hugh Ramsay exhibition.

Siggins on Ramsay

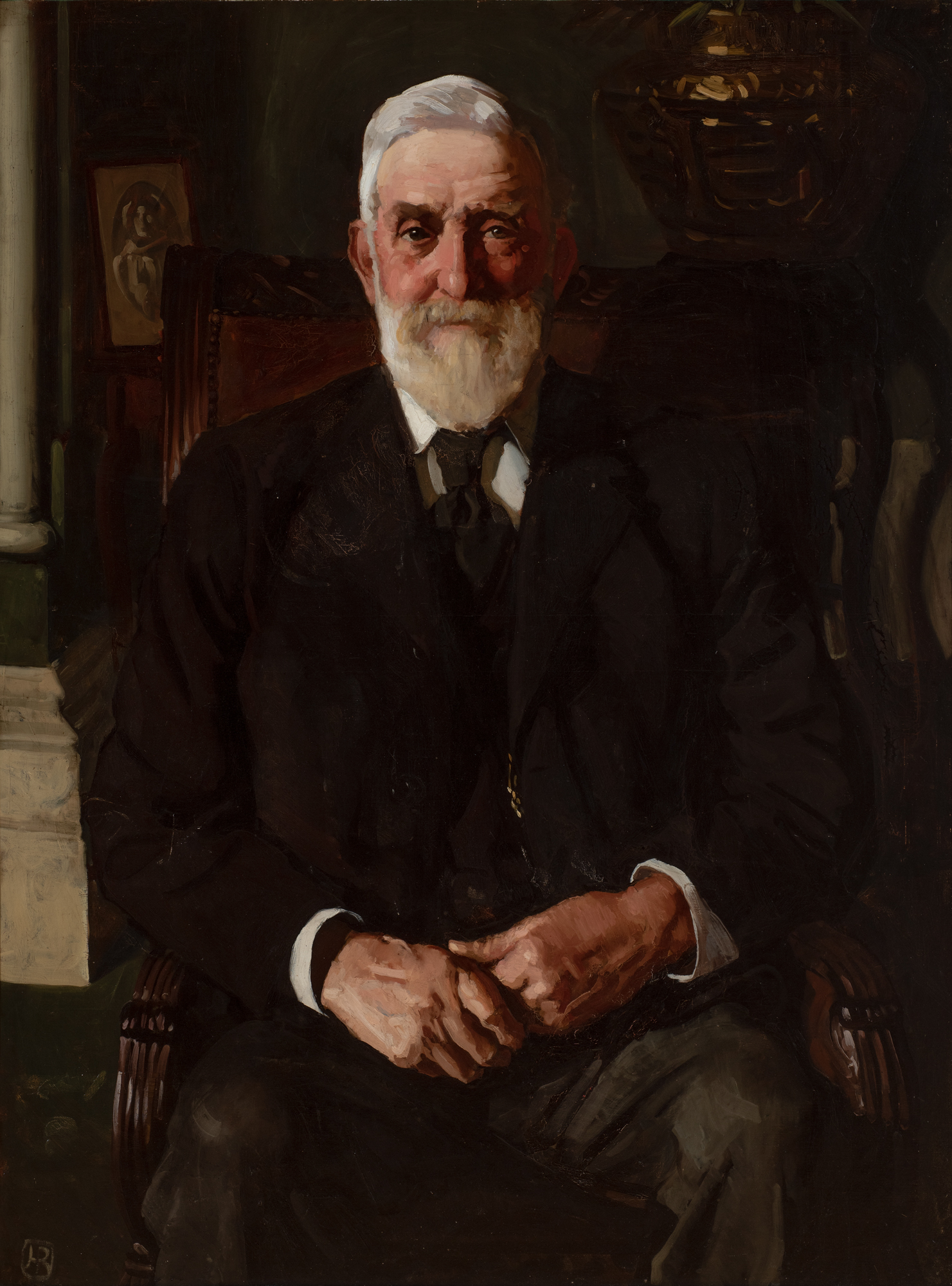

This portrait of David Mitchell—businessman, entrepreneur, father of Dame Nellie Melba—is one of the major works held by our gallery. It was commissioned by Melba and gifted by her to the gallery in 1924. It sits well with Violet Teague’s Portrait of a Pioneer and is Jupiter to the lesser planets of Frederick Reynold’s Portrait of John Shirlow (1918) and Ramsay’s early Nude Study, Old Man (c.1900).

In Ramsay’s portrait there is a quiet sense of David Mitchell’s deep past, of achievements won through resilience and hard work, and of hard won wealth. Note the column in the background signifying the classical past, and the various classical vessels dimly gleaming—the sort of booty a Roman general might have had displayed at his triumph. While Reynold’s Mitchell is presented as an image of a long life well lived, seated in drowsy, patriarchal contentment and leaning back from the surface, his John Shirlow surges forward, full of acumen and aggression. These portraits, at one time, hung in proximity, illuminating each other and suggesting different ways of contesting life’s challenges.

Ramsay’s Nude Study, Old Man also makes an interesting contrast with his later David Mitchell portrait. This nude figure study dates back to Ramsay’s student days under Bernard Hall and is a remarkably mature portrait. The pose reflects Rodin’s The Thinker. Life models for the National Gallery of Victoria Art School were paid frugally, and this old fellow could well be someone who came in off the street looking for work or a handout. Ramsay has combined the image of humble age with wisdom in a time-honoured way. It’s an image with an ancient heritage—from Rembrandt, to representation of saints (particularly St Jerome), to Socrates and his noble death. Something of a wise and kindly aura hangs about David Mitchell as well.

Hugh Ramsay was born in Glasgow in 1877 and arrived in Australia with his family in 1878. He studied at the gallery school from 1894 to 1899. After being runner-up for the National Gallery Travelling Scholarship, he travelled to Paris, meeting fellow art student George Lambert on the voyage; together, they studied old master paintings in the Louvre. Ramsay responded strongly to Velazquez and was influenced by contemporaries such as James Abbott McNeill Whistler and John Singer Sargent. In Paris he enjoyed notable success but his health broke down. Under Melba’s patronage he moved to London but was unable to go on, having been diagnosed with tuberculosis, and Melba contributed a hundred pounds towards his fare back to Victoria. She also paid the costs of his return home exhibition in Melbourne.

Ramsay returned to Melbourne in 1902, ill but full of frenetic energy. This portrait of Dame Nellie Melba’s father was completed in 1903. David Mitchell was 75 years old and had recently suffered a stroke. Considering his sitter’s drowsiness, Ramsay managed a dignified portrayal of the old man’s tired face with its heavy eyelids. The hardworking hands that Mitchell had used in his building and quarry business were painted even more realistically. Melba complained about the rough appearance of her father’s hands and asked Ramsay to repaint them. Ramsay is reputed to have responded that they were the hands of a workman. “All I could do is to paint gloves on them,” he is said to have responded. Melba wasn’t pleased but continued to sponsor Ramsay. I’m glad that gloves weren’t painted on them.

Ramsay is a tonalist in the sense that he was strongly influenced by old master painters and Whistler’s American tonalism. Velazquez painted the Spanish royal family with surprising candour, Hapsburg warts, massive chins and squinty eyes—not a flattering look. Ramsay, who studied Velazquez, learned from this, and in the depiction of David Mitchell is equally frank even down to his working-class hands.

Four years after completing the portrait of David Mitchell, Hugh Ramsay would be dead, aged twenty-eight. He was nursed to the last by his devoted sister Jessie, who, four years later, aged twenty-two, followed him to the grave with the same illness.

Brilliantly talented, musical, humorous and charming, his sojourn in Paris had yielded Salon success but under conditions of great hardship. His rescue from a freezing Paris studio by the great diva of the age (recently mistress of the Duc d’Orleans, pretender to the French throne) and his tragically shortened life were worthy of a Puccini opera. He is regarded as the Australian Sargent. Who knows what he would have accomplished, had he lived …

Phillip Siggins

February 2021

This portrait of David Mitchell—businessman, entrepreneur, father of Dame Nellie Melba—is one of the major works held by our gallery. It was commissioned by Melba and gifted by her to the gallery in 1924. It sits well with Violet Teague’s Portrait of a Pioneer and is Jupiter to the lesser planets of Frederick Reynold’s Portrait of John Shirlow (1918) and Ramsay’s early Nude Study, Old Man (c.1900).

In Ramsay’s portrait there is a quiet sense of David Mitchell’s deep past, of achievements won through resilience and hard work, and of hard won wealth. Note the column in the background signifying the classical past, and the various classical vessels dimly gleaming—the sort of booty a Roman general might have had displayed at his triumph. While Reynold’s Mitchell is presented as an image of a long life well lived, seated in drowsy, patriarchal contentment and leaning back from the surface, his John Shirlow surges forward, full of acumen and aggression. These portraits, at one time, hung in proximity, illuminating each other and suggesting different ways of contesting life’s challenges.

Ramsay’s Nude Study, Old Man also makes an interesting contrast with his later David Mitchell portrait. This nude figure study dates back to Ramsay’s student days under Bernard Hall and is a remarkably mature portrait. The pose reflects Rodin’s The Thinker. Life models for the National Gallery of Victoria Art School were paid frugally, and this old fellow could well be someone who came in off the street looking for work or a handout. Ramsay has combined the image of humble age with wisdom in a time-honoured way. It’s an image with an ancient heritage—from Rembrandt, to representation of saints (particularly St Jerome), to Socrates and his noble death. Something of a wise and kindly aura hangs about David Mitchell as well.

Hugh Ramsay was born in Glasgow in 1877 and arrived in Australia with his family in 1878. He studied at the gallery school from 1894 to 1899. After being runner-up for the National Gallery Travelling Scholarship, he travelled to Paris, meeting fellow art student George Lambert on the voyage; together, they studied old master paintings in the Louvre. Ramsay responded strongly to Velazquez and was influenced by contemporaries such as James Abbott McNeill Whistler and John Singer Sargent. In Paris he enjoyed notable success but his health broke down. Under Melba’s patronage he moved to London but was unable to go on, having been diagnosed with tuberculosis, and Melba contributed a hundred pounds towards his fare back to Victoria. She also paid the costs of his return home exhibition in Melbourne.

This portrait of David Mitchell—businessman, entrepreneur, father of Dame Nellie Melba—is one of the major works held by our gallery. It was commissioned by Melba and gifted by her to the gallery in 1924. It sits well with Violet Teague’s Portrait of a Pioneer and is Jupiter to the lesser planets of Frederick Reynold’s Portrait of John Shirlow (1918) and Ramsay’s early Nude Study, Old Man (c.1900).

In Ramsay’s portrait there is a quiet sense of David Mitchell’s deep past, of achievements won through resilience and hard work, and of hard won wealth. Note the column in the background signifying the classical past, and the various classical vessels dimly gleaming—the sort of booty a Roman general might have had displayed at his triumph. While Reynold’s Mitchell is presented as an image of a long life well lived, seated in drowsy, patriarchal contentment and leaning back from the surface, his John Shirlow surges forward, full of acumen and aggression. These portraits, at one time, hung in proximity, illuminating each other and suggesting different ways of contesting life’s challenges.

Ramsay’s Nude Study, Old Man also makes an interesting contrast with his later David Mitchell portrait. This nude figure study dates back to Ramsay’s student days under Bernard Hall and is a remarkably mature portrait. The pose reflects Rodin’s The Thinker. Life models for the National Gallery of Victoria Art School were paid frugally, and this old fellow could well be someone who came in off the street looking for work or a handout. Ramsay has combined the image of humble age with wisdom in a time-honoured way. It’s an image with an ancient heritage—from Rembrandt, to representation of saints (particularly St Jerome), to Socrates and his noble death. Something of a wise and kindly aura hangs about David Mitchell as well.

Hugh Ramsay was born in Glasgow in 1877 and arrived in Australia with his family in 1878. He studied at the gallery school from 1894 to 1899. After being runner-up for the National Gallery Travelling Scholarship, he travelled to Paris, meeting fellow art student George Lambert on the voyage; together, they studied old master paintings in the Louvre. Ramsay responded strongly to Velazquez and was influenced by contemporaries such as James Abbott McNeill Whistler and John Singer Sargent. In Paris he enjoyed notable success but his health broke down. Under Melba’s patronage he moved to London but was unable to go on, having been diagnosed with tuberculosis, and Melba contributed a hundred pounds towards his fare back to Victoria. She also paid the costs of his return home exhibition in Melbourne.

This portrait of David Mitchell—businessman, entrepreneur, father of Dame Nellie Melba—is one of the major works held by our gallery. It was commissioned by Melba and gifted by her to the gallery in 1924. It sits well with Violet Teague’s Portrait of a Pioneer and is Jupiter to the lesser planets of Frederick Reynold’s Portrait of John Shirlow (1918) and Ramsay’s early Nude Study, Old Man (c.1900).

In Ramsay’s portrait there is a quiet sense of David Mitchell’s deep past, of achievements won through resilience and hard work, and of hard won wealth. Note the column in the background signifying the classical past, and the various classical vessels dimly gleaming—the sort of booty a Roman general might have had displayed at his triumph. While Reynold’s Mitchell is presented as an image of a long life well lived, seated in drowsy, patriarchal contentment and leaning back from the surface, his John Shirlow surges forward, full of acumen and aggression. These portraits, at one time, hung in proximity, illuminating each other and suggesting different ways of contesting life’s challenges.

Ramsay’s Nude Study, Old Man also makes an interesting contrast with his later David Mitchell portrait. This nude figure study dates back to Ramsay’s student days under Bernard Hall and is a remarkably mature portrait. The pose reflects Rodin’s The Thinker. Life models for the National Gallery of Victoria Art School were paid frugally, and this old fellow could well be someone who came in off the street looking for work or a handout. Ramsay has combined the image of humble age with wisdom in a time-honoured way. It’s an image with an ancient heritage—from Rembrandt, to representation of saints (particularly St Jerome), to Socrates and his noble death. Something of a wise and kindly aura hangs about David Mitchell as well.

Hugh Ramsay was born in Glasgow in 1877 and arrived in Australia with his family in 1878. He studied at the gallery school from 1894 to 1899. After being runner-up for the National Gallery Travelling Scholarship, he travelled to Paris, meeting fellow art student George Lambert on the voyage; together, they studied old master paintings in the Louvre. Ramsay responded strongly to Velazquez and was influenced by contemporaries such as James Abbott McNeill Whistler and John Singer Sargent. In Paris he enjoyed notable success but his health broke down. Under Melba’s patronage he moved to London but was unable to go on, having been diagnosed with tuberculosis, and Melba contributed a hundred pounds towards his fare back to Victoria. She also paid the costs of his return home exhibition in Melbourne.

This portrait of David Mitchell—businessman, entrepreneur, father of Dame Nellie Melba—is one of the major works held by our gallery. It was commissioned by Melba and gifted by her to the gallery in 1924. It sits well with Violet Teague’s Portrait of a Pioneer and is Jupiter to the lesser planets of Frederick Reynold’s Portrait of John Shirlow (1918) and Ramsay’s early Nude Study, Old Man (c.1900).

In Ramsay’s portrait there is a quiet sense of David Mitchell’s deep past, of achievements won through resilience and hard work, and of hard won wealth. Note the column in the background signifying the classical past, and the various classical vessels dimly gleaming—the sort of booty a Roman general might have had displayed at his triumph. While Reynold’s Mitchell is presented as an image of a long life well lived, seated in drowsy, patriarchal contentment and leaning back from the surface, his John Shirlow surges forward, full of acumen and aggression. These portraits, at one time, hung in proximity, illuminating each other and suggesting different ways of contesting life’s challenges.

Ramsay’s Nude Study, Old Man also makes an interesting contrast with his later David Mitchell portrait. This nude figure study dates back to Ramsay’s student days under Bernard Hall and is a remarkably mature portrait. The pose reflects Rodin’s The Thinker. Life models for the National Gallery of Victoria Art School were paid frugally, and this old fellow could well be someone who came in off the street looking for work or a handout. Ramsay has combined the image of humble age with wisdom in a time-honoured way. It’s an image with an ancient heritage—from Rembrandt, to representation of saints (particularly St Jerome), to Socrates and his noble death. Something of a wise and kindly aura hangs about David Mitchell as well.

Hugh Ramsay was born in Glasgow in 1877 and arrived in Australia with his family in 1878. He studied at the gallery school from 1894 to 1899. After being runner-up for the National Gallery Travelling Scholarship, he travelled to Paris, meeting fellow art student George Lambert on the voyage; together, they studied old master paintings in the Louvre. Ramsay responded strongly to Velazquez and was influenced by contemporaries such as James Abbott McNeill Whistler and John Singer Sargent. In Paris he enjoyed notable success but his health broke down. Under Melba’s patronage he moved to London but was unable to go on, having been diagnosed with tuberculosis, and Melba contributed a hundred pounds towards his fare back to Victoria. She also paid the costs of his return home exhibition in Melbourne.