Reflections - On the significance of frames

Surrounding CAM’s celebrated collection of artworks is an equally intriguing and important collection of frames. Last year, CAM honorary conservator Deborah Peart conducted a frame-cleaning workshop with volunteers to prepare works from the collection for the upcoming exhibitions: The Unquiet Landscape and Janina Green in conversation with the Collection.

As frames are to the work of art, volunteers are to cultural organisations: offering critical support however, volunteers are not always as visible. In this, National Volunteer Week, we are pleased to bring you Deborah Peart’s reflection on the significance of frames. Peart is driving CAM policies and practice around caring for frames. As part of CAM’s Digital Roadshow (supported by Creative Victoria), Peart introduces some of the surprising issues surrounding the new-found respect, research and care given to frames.

On the significance of frames

Surrounding CAM’s celebrated collection of artworks is an equally intriguing and important collection of frames. Last year, CAM honorary conservator Deborah Peart conducted a frame-cleaning workshop with volunteers to prepare works from the collection for the upcoming exhibitions: The Unquiet Landscape and Janina Green in conversation with the Collection.

As frames are to the work of art, volunteers are to cultural organisations: offering critical support however, volunteers are not always as visible. In this, National Volunteer Week, we are pleased to bring you Deborah Peart’s reflection on the significance of frames. Peart is driving CAM policies and practice around caring for frames. As part of CAM’s Digital Roadshow (supported by Creative Victoria), Peart introduces some of the surprising issues surrounding the new-found respect, research and care given to frames.

Frames provide a physical boundary around a two-dimensional work of art, as well as defining an area of transition between the work and the surrounding room. For many people, frames are a secondary feature compared to the painting or work on paper and are frequently unnoticed. Yet a frame can make a dramatic impact on the reading of an artwork, achieving an aesthetic balance with the work. Frame selection is no easy task for an artist or curator. Frames now offer an exciting area for academic research and practical care.

Like art itself, frames are subject to fluctuations in tastes and fashion. The common past practice of frame removal, disposal and replacement with different or standard frames for convenience of storage or uniformity in exhibition design failed to recognise the artist’s intent, the historical context, or the integral relationship between the original work and the frame. Past inappropriate treatments, overpainting with bronze paint, and oil regilding have depleted the cultural value of antique frames.

Over the last decades, museums and galleries have dramatically reversed previous attitudes towards frames, declaring frames as a legitimate area of study and conservation science, in recognition of their artistic, historical and cultural significance. Now, conservators, curators and skilled artisan frame-makers extensively conserve, acquire and reproduce frames based on more nuanced understandings of materials and of the relationship between painting and frame. Knowledge of historical materials and techniques assists in understanding their ageing and vulnerabilities.

Designed to protect and distinguish the work of art, ageing frames can pose a challenge for museums and galleries, as the vulnerable components are sensitive to water and other cleaning methods, abrasions and knocks.

Background

Early European picture frames of the thirteenth century were modest structures designed to protect sacred paintings. As paintings were introduced into secular life, attention to their design, materials and techniques became more important, culminating in the high levels of design and craftsmanship of exuberantly carved and decorated gilt frames from the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century Italian and French Rococo periods.

Early Australian frames were made of local timbers with a gilded slip (a separate frame construction that fits into the rebate or inner edge of the frame). By the late 1880s, with the influx of skilled frame-makers and components from the United Kingdom and Europe, Australian gilded frames were following European trends such as classical revival and renaissance styles. Prior to 1930, the generally accepted type of frame was gilded wood, essentially comprised of gold, silver leaf or alloys of metals on a constructed substrate of gesso (a chalk mix) on a wooden frame.

CAM frames

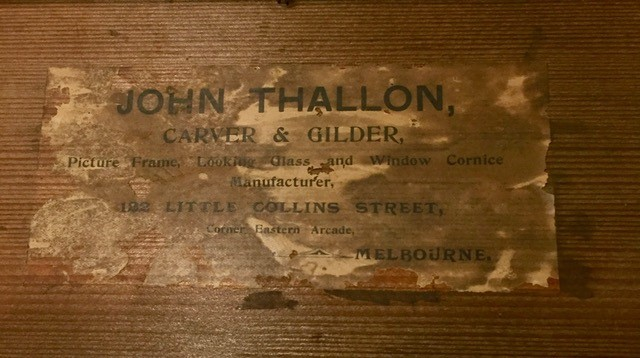

Individual frames in the CAM collection viewed during the workshop reflect aspects of local and international artistic and cultural life. Labels from Melbourne’s leading painting frame-maker, John Thallon (1848–1918), were observed on a number of frames, including on John Ford Paterson, Fernshaw, 1896; Bernard Hall, Sketch for Sleep, 1906; Sydney Long, Pastoral Landscape, 1909; and Clarice Beckett paintings of the 1920s.

Despite many Australian artists turning to the more economical machine-embossed timber with decorated pressed composition moulded frames from the 1850s, some artists and framers were influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites, and the art and crafts movement explored gilding on un-gessoed wood, so the wood grain effect became more apparent. CAM has an intriguing example in a handmade and carved frame in the collection by artist John Farmer (1897–1989). Because CAM was a trendsetter in the early days, a frame study of the collection may unearth some gems. For example, does CAM hold any frames by Lillie Williamson (Tom Roberts’ wife) an accomplished wood-carver and frame-maker? Art Nouveau and Art Deco designs are also evidenced in CAM frames.

Vulnerable objects

As composite objects, frames are vulnerable to damage and deterioration. For example, the underlying wooden structure moves differently with fluctuations in temperature and relative humidity compared to movement in the outer layers, resulting over time in swelling, shrinking, twisting, separation and cracking. The drying of animal glue and oils leads to reduced adhesion within and between the layers, resulting in flaking and loss of the gilding. High humidity can encourage mould growth in the varnish, leaving black or green stains on the wood and black dirt. Colourants can fade, particularly in ultraviolet light, and the metal gilding is subject to tarnish and corrosion due to various conditions. Preventive conservation is the key to caring for frames. This includes environmental management and safe handling to avoid and minimise deterioration and loss.

Deborah Peart

May 2020