Reflections on historic photography in the collection

CAM’s Honorary Conservator, Deborah Peart, returns with another insight into the historical collection, this time considering CAM’s historical photographs. You can read Deborah’s earlier pieces on Footwear and Frames. This reflection is supported by the Victorian Government through Creative Victoria’s Digitisation Roadshow program.

As many of us reflect on forced workplace change during 2020, the Thompson’s Foundry Interior print provides an engaging “look” into a different workspace of the past.

The CAM historical photographic collection is mixed, reflecting the evolutionary nature of photographic technology since the 1850s. Of note are the glass plate negatives, lantern slides, ambrotypes, albumen prints, opaltypes and gelatin silver prints. Offering a valuable study resource, the collection provides visual insights into Castlemaine’s past and social conventions. Subject matter is diverse: goldmining, employment, transport, street scenes, historic and social events, and people. There are portraits, family snaps, panoramas, art photography and more.

The photographic process generally utilises a transparent emulsion layer sensitised with silver salts (either silver chloride, silver bromide or silver iodide) on a base layer of either paper, glass or metal. On exposure to light, the light-sensitive silver salts in exposed areas decompose to produce metallic silver, which makes up the image. Typical emulsion layers are albumen (egg white), collodion (cellulose nitrate, ether and alcohol) and gelatine.

Institutions and home collectors face challenges to safeguard image stability and preserve their fragile photographic collections. Due to a photograph’s inherent susceptibility to deterioration, a stable storage environment is paramount in slowing degradation. Fluctuating environments with higher temperatures and humidity levels and atmospheric pollutants promote deterioration. Light damage is cumulative and irreversible, especially from the ultraviolet (UV) component in visible light. Salted paper, albumen and colour prints are particularly susceptible to light damage. A clean, dark, cool, relatively dry environment (30–40% Relative Humidity [RH]) off floors and away from basements, attics and external walls is recommended. Many photographic materials with certain sensitivities require specific approaches to handling, housing and storage.

Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre introduced the world to photography in 1839 with the daguerreotype. This mirror-like positive image appears on a highly polished silver-plated copper sheet, sealed in a glazed, leather and velvet hinged case. The ambrotype, also a cased image, was produced as a negative image in emulsion on glass. The glass was backed with either black paint, fabric or paper to produce a positive image. Deteriorating paint and emulsion layers contribute to image loss. Images of the two intriguing ambrotypes above depict gold and colour hand-tinting.

Images of Castlemaine Market Building often feature in the collection. The above albumen print presents an uncluttered view of the imposing building soon after construction in 1862. Albumen prints dominated the second half of the 19th century. Processing by contact printing, from glass plate negatives, on printing-out paper was time consuming. These ageing prints are susceptible to chemical deterioration resulting in image fade, detail loss, and yellowing or staining, combined with physical crazing and cracking of the albumen emulsion. The above print has suffered from a central tear, flaking, staining and discolouration, and the mount has significant silverfish damage. The interesting print below of the hotel in Campbells Creek has characteristic fading and staining, including grime stains from poor handling.

With a tendency to curl, albumen prints on thin high-quality papers were frequently mounted on poor-quality lignified backing boards with poor-quality adhesives during manufacture. These boards become more acidic, discoloured and embrittled, often with foxing (localised discolouration spots). Removal of a board that potentially compromises a print can threaten the print’s historical, aesthetic and physical integrity. Treatment decisions can be complex.

The photograph above shows a distracting pattern of foxing, which is exacerbated by acid transfer. This highlights the need for separation of photographs during storage.

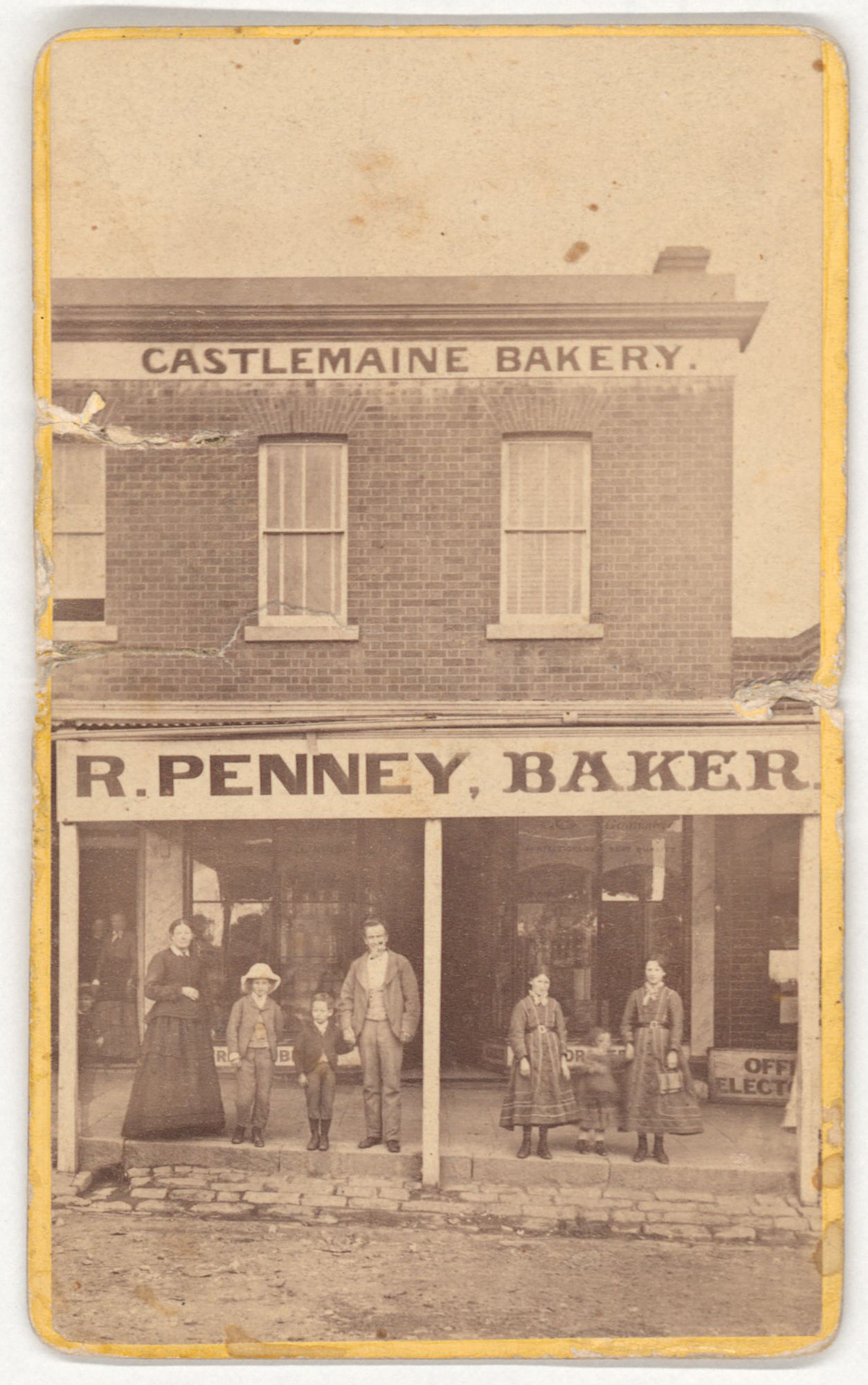

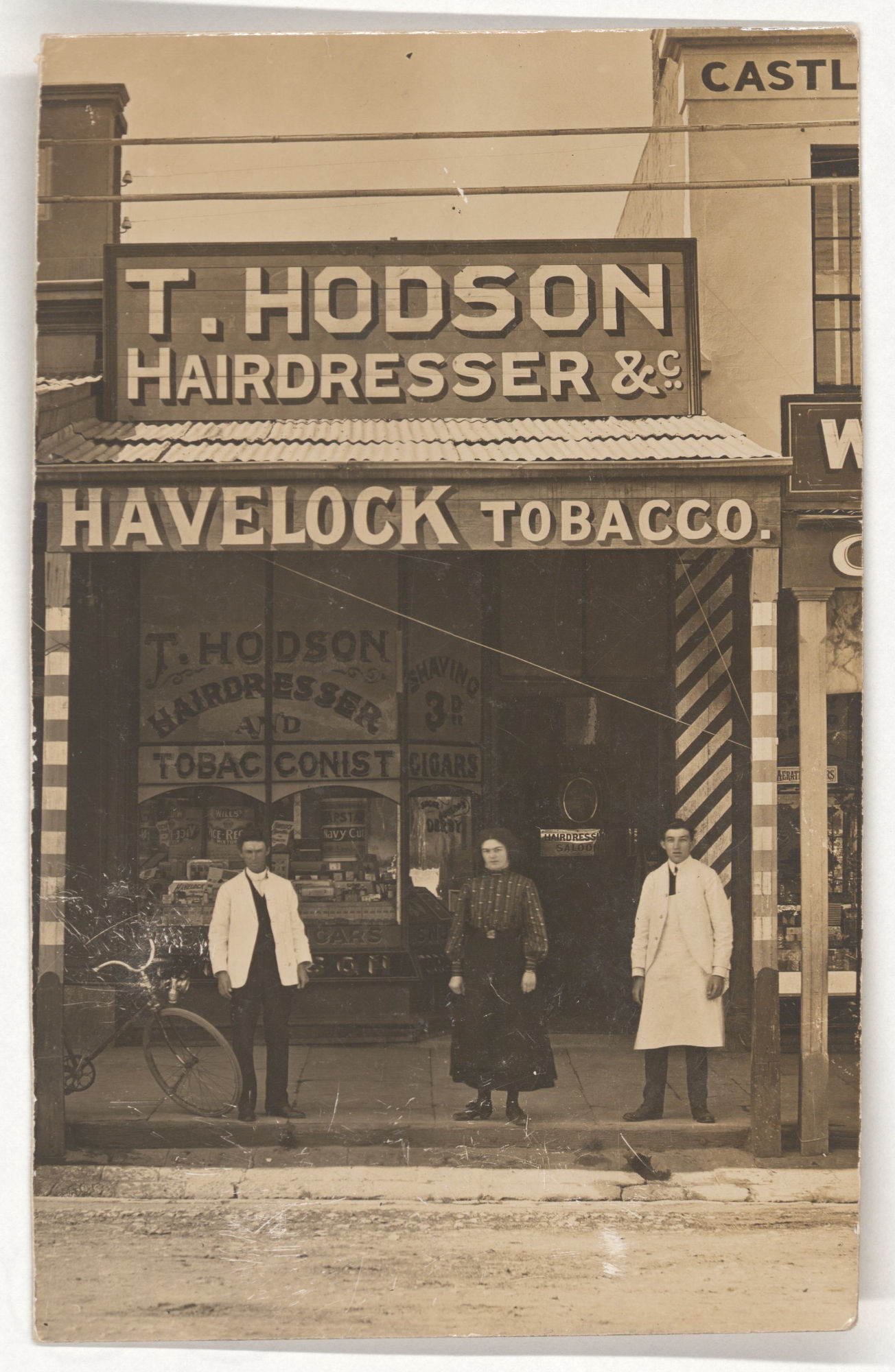

In phases from 1860 to 1930s, small cartes de visite (64 x 100 mm), postcards and the larger cabinet cards were popular. Their backing cards are integral and provide valuable information. Two postcard-sized prints of local businesses above provide a comparison between an earlier albumen print (left) and the gelatin silver print (right) that became the standard technique in the 20th century.

The gelatin silver printing process using developing-out paper, an enlarger, negatives and chemical “developer” has benefits, including shorter processing time. Gelatin prints are very sensitive to moisture fluctuations, swelling, shrinking and curling. Unfavourable conditions contribute to mould growth, stickiness, flaking and chemical reactions causing silver mirroring (when silver migrates to the emulsion surface), particularly in prints produced between 1910 and 1940.

The above unfortunate print displays the consequences of high RH exposure or moisture infiltration—toxic mould, silverfish damage, discolouration, distortion, separation and loss.

Preservation of the emulsion surface reflectance and integrity is critical for a print’s aesthetic value. Protecting the surface quality, gloss or matt, lustre and texture requires abrasion prevention and safe handling with gloves. Photographic storage generally involves a multi-layered enclosure system: prints are individually sleeved in inert plastic (uncoated polyester, polypropylene or polyethylene, not PVC), interleaved or wrapped in a seamless four-flap enclosure in archival-quality, acid-free, unbuffered papers. Damaged prints require special attention.

Archival, acid-free boxes provide a further buffer from the external environment, dust, insect ingress and light. To reduce stress, enclosed loose small prints store well vertically supported in suitably sized boxes, while larger prints are best stored flat in larger shallow boxes, according to size. Archival-quality albums offer long-term protection compared with the self-adhesive type. Sticky tape, adhesives, clips and pens pose a risk to the longevity of valuable photographs.Digitisation importantly records the image, enabling safe sharing with a wider audience. The imperative is to complete the task of archival housing of the remainder of CAM’s unique, original photographic material.

Deborah Peart

October 2020