Onus on repatriating First Nations knowledge

In recognition of NAIDOC week, CAM Board member Tiriki Onus (Yorta Yorta, Dja Dja Wurrung) proposes a new way of thinking about First Nations artefacts held in museum collections. Onus brings a remarkably broad range of experience as a visual artist, musician and educator to leading a discussion about the role of objects in the proud repatriation of Indigenous knowledge.

Onus on repatriating First Nations knowledge

Museums and First Nations knowledge

When the National Museum of Australia (NMA) mounted its Encounters exhibition in the summer of 2015/16, First Nations groups felt an ambivalent sense of pride, fear, hunger and loss. One hundred and fifty-one objects representing 27 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations were brought from the British Museum’s storage and displayed on Ngunnawal Country in Canberra. In an attempt to acknowledge the provenance of this extraordinary collection and to give First Nations communities a greater sense of cultural safety, the NMA invited Indigenous curators and representatives from the homelands of these objects to participate in realising the exhibition. The British Museum agreed, but there was a caveat: only their own curators and conservators were permitted to touch or handle the work.

After being separated from objects which our grandmothers and grandfathers had poured themselves into generations ago, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representatives (including many well-established curators from major institutions across Australia) were required to stand back and observe. For Indigenous communities, these may have been significant and tangible links to a culture and identity which has survived despite over two centuries of bitter and protracted attempts at erasure. But considered through the dominant cultural lens, these were museum artefacts, relics of a forgotten past which must be preserved in time and at all costs, and ultimately returned to the British Museum storage.

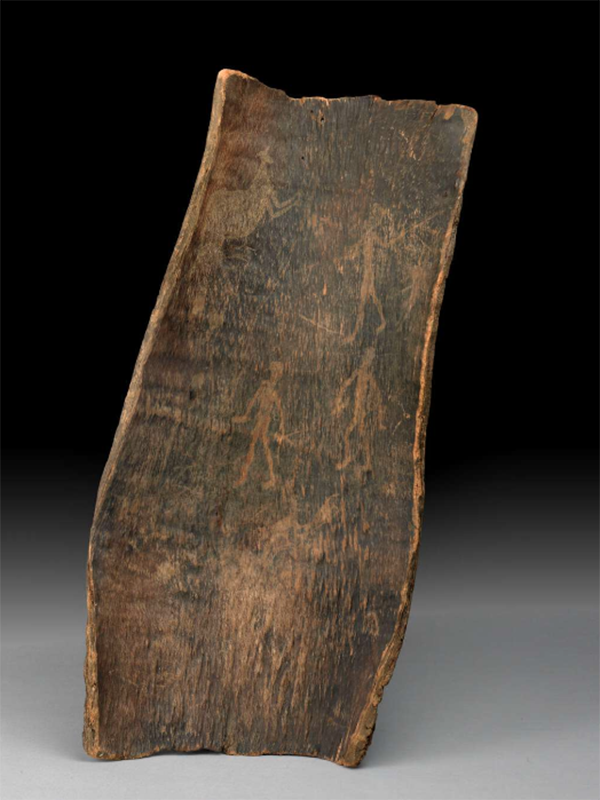

Visiting the exhibition, I stood mesmerised by the intricate and deft etching on a bark from my own Dja Dja Wurrung Country. Struck by the weight of story and history that sat behind a sheet of toughened glass in front of me, I wondered about the hands that made those incisions. How did they know when (and how) to collect the materials? How many iterations of technology and process had to be experimented with before the techniques of curing and flattening the bark were fully understood? Who the heck was genius enough to try in the first place?

As an artist obsessed with reclaiming the technologies and practice of my forebears, museums have become (at times) an uneasy home for me, strange environments in which we are surrounded by the legacy of our families, yet in an alien atmosphere that seeks to catalogue and quantify. Viewing ourselves through the eyes of the coloniser is never easy. However, in looking past this alienating legacy, in pushing aside the ethnographic and anthropological lens which sought to record the last vestiges of a dying race, we are left with vast warehouses of knowledge and stories embodied in objects, once more waiting to be told.

As someone who views their practice as an inalienable link to both my country and identity, the objects held in museums are far from mere artefact. They are human remains: tangible repositories that offer us the opportunity to reengage with knowledge cultivated, maintained and added to, over thousands of generations. They speak—and if we listen closely—we’ll hear.

The question of repatriation of physical objects is never far removed when it comes to ethical museological practices. But for artists like me, who have made it our business to reengage with objects expropriated from our ancestral lands, there exists an often more vital question: how do we return the knowledges of our old people back to Country?

Far from viewing the fraught historical relationship between museums and First Nations peoples as a problem, it can instead be seen as a wonderful opportunity. This will only happen, however, if we are bold enough to shift our positions and move beyond what we have been taught, and largely accept to be true. We can allow ourselves the opportunity to revel in the sophistication, genius and diplomacy that was required to bring life to these pieces of Country. When we collectively see ourselves as empowered agents of change who have the ability to open our minds and (more importantly) our institutions’ doors to the process of actively reviving and repatriating the knowledges contained within, we all win. After all, it is the countries we now all call home in which these stories belong, and we can all play a part in their revitalisation.

When we disconnect ourselves from the life of an object, and seek only to “protect” it by putting it behind glass, without engaging with its function, purpose, and voice, is it still the same? When does a spear that isn’t thrown cease to be a spear, and become a mere stick?

Tiriki Onus

November 2020