On the Castlemaine Art Gallery and the ‘Museum Movement’

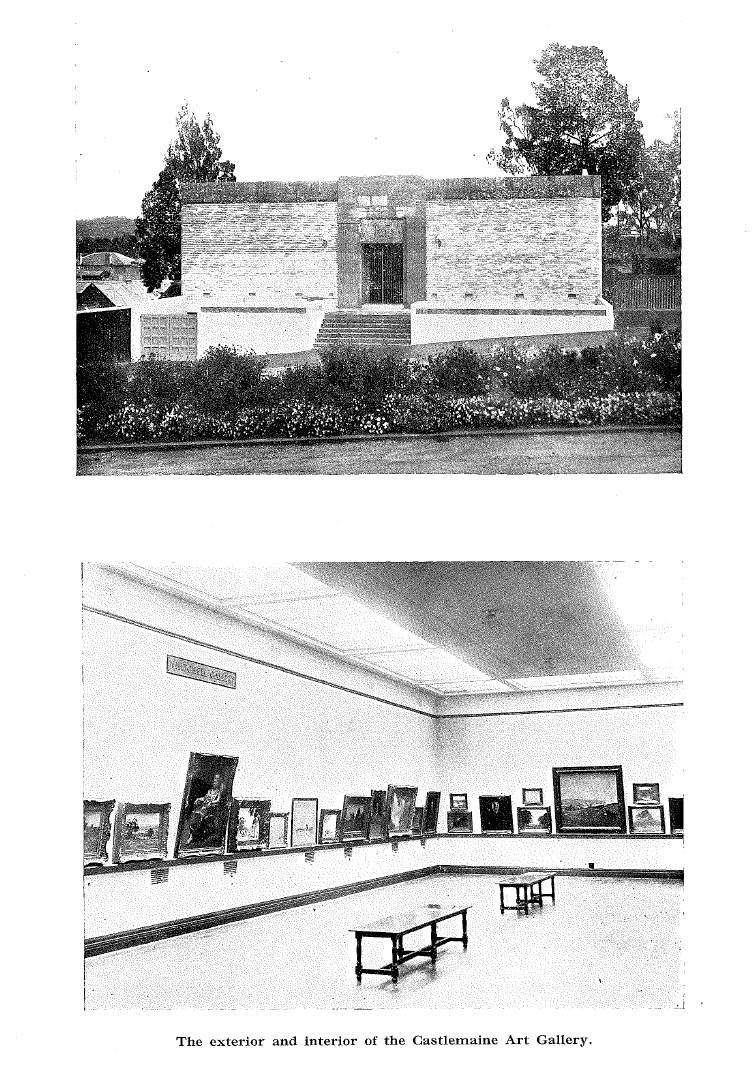

Local academic Ian McShane explores why a British MP sponsored by one of America's most influential philanthropists was singing the praises of the newly opened Castlemaine Gallery in 1933. We look forward to learning more about this relationship following Dr McShane forthcoming research in the CAM archives. It is interesting to note that the photograph of the Whitchell Gallery below was taken prior to the Higgins Gallery being built and that the benches which are still in use, also date from this period.

These two images of the newly opened Castlemaine Museum and Gallery are taken from a 1933 report on museums and galleries in Australia, funded by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The self-educated steel magnate Andrew Carnegie’s (1835-1919) interest in public libraries is well known. His philanthropy funded around 2,500 public library buildings in the USA and the British Empire and was largely responsible for establishing the New York Public Library Service.

We are less familiar, though, with the philanthropy’s support of the ‘museum movement’, as the museum report described it, or a campaign for the revitalisation and reform of museums and galleries as key elements of civic, cultural and educational life. The museum movement is the subject of a book I am researching that will help fill a gap in our understanding of this period in the history of collecting institutions.

Why did the report single out Castlemaine for special mention? Australia was included in a series of Carnegie-funded inquiries undertaken in the British Empire and the USA, the countries of the “English-speaking race”, as Andrew Carnegie termed it. The museum movement argued for the significance of museums in fusing local settler histories with new topics such as town planning and public health. Galleries played a role in raising aesthetic sensibility, which would be subsequently demonstrated in tasteful home furnishings. Museums and galleries, then, had a key role to play in instruction and civic uplift, their visual settings appealing particularly to “poor book learners”, in the report’s words. Local support for these institutions was also a measure of civic leadership, argued the report, and on this measure many regional centres were found wanting.

One of the movement’s principal evangelists and author of the Australian report, Frank Markham (1897–1975), was a UK parliamentarian and secretary of the Carnegie-funded Museums Association. Markham, who started out as a market barrow boy but graduated from Oxford University following war service, had an enduring interest in museums; his views on their role in personal and civic uplift echoed those of Andrew Carnegie. He convinced the New York-based philanthropy to fund a series of inquiries into museums in the British Empire, which brought him to Australia. Markham was generally scathing about the state of Australian museums and galleries. Smaller towns, and even some major cities “have over-crowded, badly selected and uncurated collections that fortunately do not attract the public”1, the report stated. It continued

(t)he lack of competent and frequent curatorial work in many of these museums is a severe handicap to the progress of the museum movement in the country districts.2

For Markham, though, Castlemaine showed what was possible. Local fundraising efforts enabled the new building to open during a global depression. Its modern design broke with the neo-Classicism that many Australian gallery and museum buildings adopted to establish their cultural authority. With its well-chosen, well-spaced and “fairly well labelled” pictures (he was a stern critic) “this small town has probably a better art gallery than any comparable town in the British Empire.3

The Australian museums inquiry did not have the impact of a similar Carnegie-funded inquiry into Australian libraries conducted in 1934, which underpinned subsequent development of municipal libraries. Funding that flowed from the museum report was largely directed to the training of professional staff and study tours. The museum inquiries bear the imprint of the Carnegie Corporation’s racial and cultural politics at that time, with their emphasis on settler history and anxiety about cultural literacy. However, the wider “museum movement”, with its progressive interests in display techniques, audiences, and the roles and value of cultural institutions, played an important role in the development of modern museology.

1 Markham, S. F. and Richards, H. C. A Report on the Museums and Art Galleries of Australia to the Carnegie Corporation of New York. London: Museums Association, 1933, p.3

2 Report, p.4

3 Report, p.33.

These two images of the newly opened Castlemaine Museum and Gallery are taken from a 1933 report on museums and galleries in Australia, funded by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The self-educated steel magnate Andrew Carnegie’s (1835-1919) interest in public libraries is well known. His philanthropy funded around 2,500 public library buildings in the USA and the British Empire and was largely responsible for establishing the New York Public Library Service.We are less familiar, though, with the philanthropy’s support of the ‘museum movement’, as the museum report described it, or a campaign for the revitalisation and reform of museums and galleries as key elements of civic, cultural and educational life. The museum movement is the subject of a book I am researching that will help fill a gap in our understanding of this period in the history of collecting institutions. Why did the report single out Castlemaine for special mention? Australia was included in a series of Carnegie-funded inquiries undertaken in the British Empire and the USA, the countries of the “English-speaking race”, as Andrew Carnegie termed it. The museum movement argued for the significance of museums in fusing local settler histories with new topics such as town planning and public health. Galleries played a role in raising aesthetic sensibility, which would be subsequently demonstrated in tasteful home furnishings. Museums and galleries, then, had a key role to play in instruction and civic uplift, their visual settings appealing particularly to “poor book learners”, in the report’s words. Local support for these institutions was also a measure of civic leadership, argued the report, and on this measure many regional centres were found wanting. One of the movement’s principal evangelists and author of the Australian report, Frank Markham (1897–1975), was a UK parliamentarian and secretary of the Carnegie-funded Museums Association. Markham, who started out as a market barrow boy but graduated from Oxford University following war service, had an enduring interest in museums; his views on their role in personal and civic uplift echoed those of Andrew Carnegie. He convinced the New York-based philanthropy to fund a series of inquiries into museums in the British Empire, which brought him to Australia. Markham was generally scathing about the state of Australian museums and galleries. Smaller towns, and even some major cities “have over-crowded, badly selected and uncurated collections that fortunately do not attract the public”1, the report stated. It continued(t)he lack of competent and frequent curatorial work in many of these museums is a severe handicap to the progress of the museum movement in the country districts.2For Markham, though, Castlemaine showed what was possible. Local fundraising efforts enabled the new building to open during a global depression. Its modern design broke with the neo-Classicism that many Australian gallery and museum buildings adopted to establish their cultural authority. With its well-chosen, well-spaced and “fairly well labelled” pictures (he was a stern critic) “this small town has probably a better art gallery than any comparable town in the British Empire.3The Australian museums inquiry did not have the impact of a similar Carnegie-funded inquiry into Australian libraries conducted in 1934, which underpinned subsequent development of municipal libraries. Funding that flowed from the museum report was largely directed to the training of professional staff and study tours. The museum inquiries bear the imprint of the Carnegie Corporation’s racial and cultural politics at that time, with their emphasis on settler history and anxiety about cultural literacy. However, the wider “museum movement”, with its progressive interests in display techniques, audiences, and the roles and value of cultural institutions, played an important role in the development of modern museology.