Nunn on Longstaff, Part 2

Last week, conservator Catherine Nunn discussed two small paintings by John Longstaff in our collection. Nunn has been researching these works for her PhD in Technical Art History/Conservation. In this Reflection, Nunn discusses her technical examination of the paintings.

Convalescence and canvases

John Longstaff's Cabbage Plot, Belle-Île, and Moonlight After Rain, Belle-Île were painted on the French island of Belle-Île in the summer of 1889. John Russell had invited Longstaff to come and stay with him there to convalesce from ‘black influenza’ which Longstaff had contracted in Paris. I have been analysing these paintings as part of my PhD research to help understand more about Australian painters working in France during this period.

During the time Longstaff painted on Belle-Île, his technique became more Impressionistic in response to the influence of Russell, who had worked with Monet and Van Gogh. This can be seen in these paintings from the CAM collection in the high-key palette and expressive technique where paint is rapidly applied with square brushes. Likewise, Longstaff’s use of small canvases for his paintings on Belle-Île reflects his adaptation to the local environment.

In major cities, canvases could be bought from artist’s colourmen (specialist art supply stores) in standard sizes, pre-stretched and ready for painting. When working in Paris, Longstaff painted on these kinds of commercially stretched canvases, but on Belle-Île he used different materials. When travelling, it would have been cumbersome to transport bulky stretched canvases, and it was probably difficult to buy them on the island. Longstaff’s works executed on Belle-Île are instead painted on loose pieces of canvas, which have subsequently been lined (adhered onto a secondary support). Longstaff probably cut these small canvases from a large roll of fabric and then pinned them onto a flat board for painting. A flat piece of canvas would have been easier to carry to the plein-air painting location and would also have been more practical to transport back to Paris after the summer.

When comparing the dimensions of Cabbage Plot, Belle-Île (27.0 x 46.0 cm), and Moonlight After Rain, Belle-Île (19.7 x 26.5 cm), the height of the larger and width of the smaller are very similar (27.0 and 26.5 cm). Accounting for some loss along the edges during the lining process, it’s likely that both pieces were originally cut from the same roll of canvas. Another painting done by Longstaff on Belle-Île, now in the National Gallery of Victoria, (Farm, Belle-Île, c. 1889, 12.2 x 25 cm) may also have been cut from this roll of canvas. This painting is of the low, whitewashed farm buildings that appear in Cabbage Plot, Belle-Île, and it is also painted on a small piece of canvas that has been adhered to a board. Comparing the dimensions of this work (width of 25 cm) with the CAM paintings, it’s probable that these three canvases were all cut from the same canvas roll, from a strip about 80cm wide.

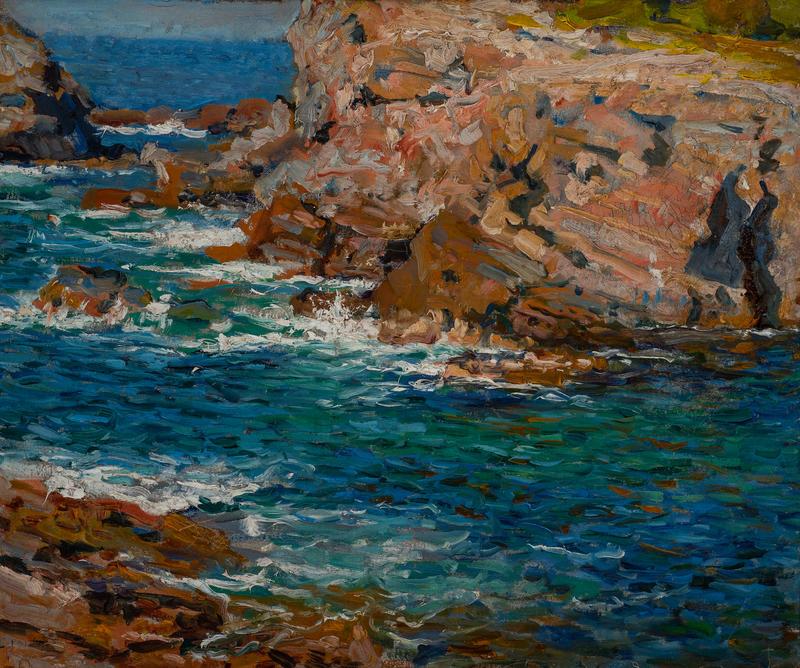

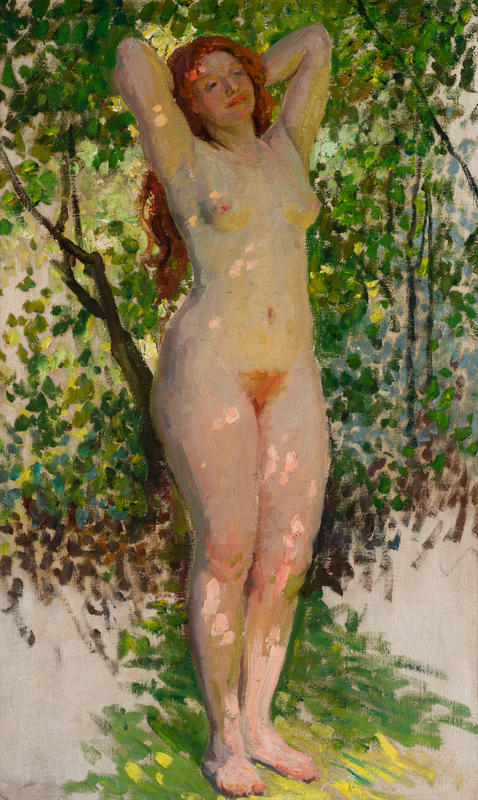

It’s not unusual for artists to modify their materials to suit the environment. For example, the Australian Impressionist painter E. Phillips Fox prepared his own canvases when he was travelling, as seen in On the Mediterranean Coast from the CAM collection. Fox painted this work while on an extended painting trip around the Mediterranean and Northern Africa with his wife Ethel Carrick. It appears that Fox originally used these canvases for practical reasons when working ‘in the field’, however, he evidently liked the resultant surface effects and they became an intentional aesthetic feature of his works. His Standing Nude in the CAM collection was painted in the garden of his Paris home (65 Boulevard Arago). It also has a home-made priming layer, which creates a matt, pastel-like surface effect. Despite painting this work in Paris, with easy access to commercially prepared canvases from his colourman (the Foinet/Lefebvre firm, situated just a few blocks away at the corner of Rue Brea and Rue Vavin), Fox instead chose to prepare this canvas himself with an absorbent priming layer. This helps to create the diffraction of light from the rough, matt surface, which contributes to the verisimilitude of the shimmering heat reflected from the model’s flesh.

While Longstaff adapted his technique to achieve a more Impressionist approach on Belle-Île, many of his other paintings have suffered from extensive cracking. This ‘alligatoring’ is caused by the different drying times of multiple paint layers, and his copy of Titian’s Entombment (Entombment of Christ (c.1888), 146.5 x 212.5, National Gallery of Victoria) is one such example. Fortunately, Longstaff’s Belle-Île works in the CAM collection do not suffer from these ills, thanks to their rapid, Impressionistic technique. However, Longstaff’s flirtation with these methods was short lived. After his time on Belle-Île, he went on to become a sought-after traditional portraitist, and most of his other works are painted on conventional, commercially stretched canvases, often with dark, labouriously applied layers, prone to cracking. In 1920 he returned permanently to Australia, and his work settled into what art historian Leigh Astbury has called a “basically academic and conservative” pattern; but on Belle-Île, his paintings were quite different.

Catherine Nunn

November 2021