Milford on Smart

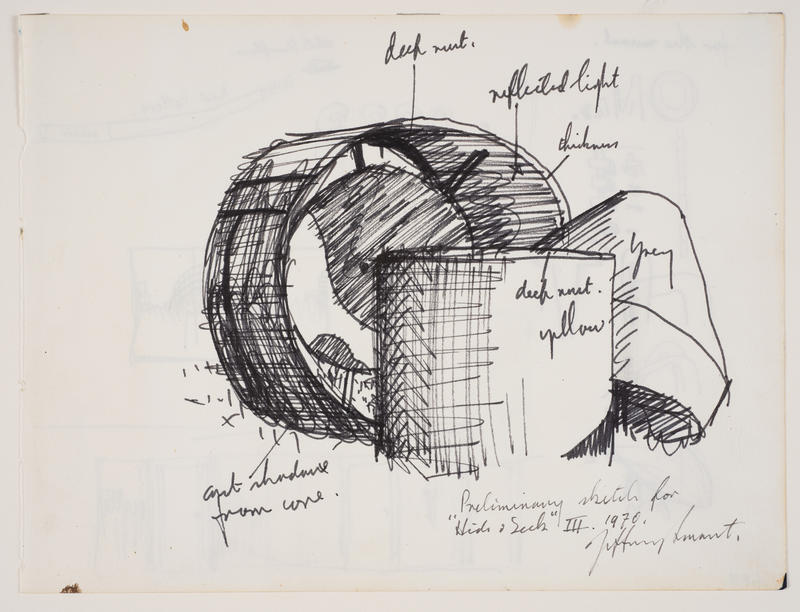

In this Reflection, George Milford shares a personal reading of one of CAM’s jewels, Hide and Seek III 1969–70, by Jeffrey Smart (1921–2013). Castlemaine holds not only this painting but also a preliminary sketch from the same year. Here, Milford reflects on how his interest in art intersected with his work. You can catch up on earlier reflections by clicking here.

Milford on Smart

For most of my working life, a framed reproduction of Jeffery Smart’s Hide and Seek III stood on my office bookshelf. There were always large pipes in the yard across from the office at the Thompson’s Foundry, Castlemaine, where I worked for many years. These pipes, monumental in diameter, were occasionally set up to enable pumps to be tested in a full-size mock-up of the customer’s on-site conditions. The central features of Smart’s painting are huge pipe-like structures. Any Thompson’s employee could relate to the scene Smart depicts.

In a letter to the museum in 1985, Jeffery Smart wrote that he had first seen the group of big metal shapes beside a road in Northern Italy.i This was a road from Parma to Sabbioneta, north of Smart’s home in Arezzo. Hide and Seek was painted when townscapes worldwide featured large, welded metal sculptures. Melbourne had a few, notably Ron Robertson-Swann’s controversial Vault 1978.

Smart writes that he was considering painting these severe geometric shapes, and in doing so he returned to a theme he first explored in 1962, of children playing a game of hide and seek in an incongruous, imposing architectural setting. In Hide and Seek 1962 (Art Gallery of Western Australia), Smart depicts the terribly repetitive and boring grey concrete columns of an underground car park (at which the Prince of Wales would shudder and exclaim brutalist architecture) as the setting for his colourful depiction of childhood play.'

Jeffery Smart is renowned for painting objects commonly dismissed as ugly, such as freeways and factories.ii They aren’t all ugly, if you look at their pure geometry. Such geometry was something to which those working at the foundry were keenly attuned. His paintings talk of the weird beauty of our surroundings.iii

But the old pipes at the foundry had no weird beauty. They were part-rusted, unused for most of the time, inert and massive, and in some ways, menacing, with great diameters, much weight and big shadows. There is a challenge for all who work in a factory environment: the machine. Managing such machinery can take over the organisation. There is always this threat.

The shapes in Smart’s painting, though colourfully coated against the elements, are set under a dark and menacing sky. By depicting children playing in this context, Smart introduces innocence and the child’s acceptance of things as they are. It is the children’s vitality that contrasts with the forms, background and sky. It is possible that Smart is being critical of modernist sculpture in public places. However, I see the contrast between Smart’s depiction of huge inert structures and playful children as a comment on the resilience of joy and humanity amid the sometimes bleak urban landscape.

George Milford

February 2013/20

i Letter from J Smart to P Perry, 1985, in CAM files

ii The Age ‘Good Weekend’, 7 August 1999

iii Desmond O’Grady, Qantas Magazine, undated article in CAM archive.