McArdle on Scott

Through the Digitisation Roadshow program, CAM has unearthed treasures to feature in publications and exhibitions. Six astonishing early photographs of Castlemaine from the local firm Verey Brothers have been digitised and three are currently showing in the Whitchell Gallery. Local artist and academic James McArdle brings his expertise in photography to shed valuable light on two cloudy ‘moonlight’ panoramas.

McArdle on Scott

Feeling the need to be useful, I’ve volunteered to be a guide at Castlemaine Art Museum, though wondering if my specialisation in photography will disadvantage me in a museum full of ceramics, painting, drawing, prints and sculpture. In preparation, I cast around CAM’s website to find out more before going to my first information session.

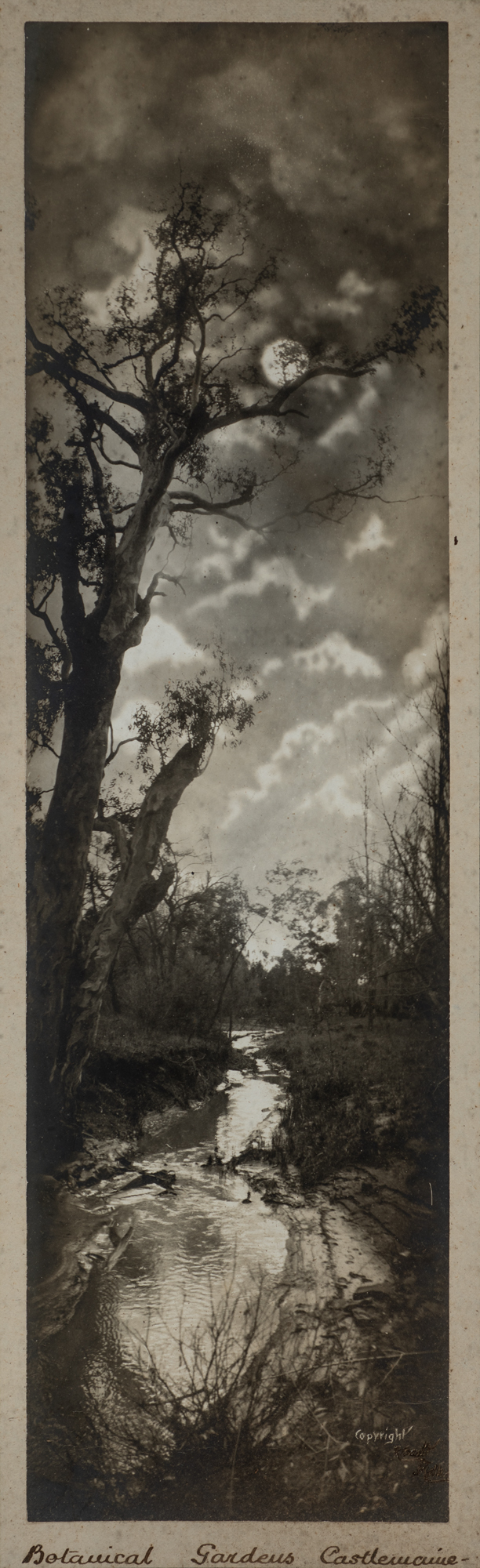

CAM’s annual report for 2019/20 contains a pleasant surprise, a lovely example of Federation-era pictorialism. It’s a rare vertical panorama, when most such views, like that on the next page of the report, are horizontal.

As a bonus, this and the companion works are of Castlemaine itself. Two capture our botanical gardens, which look not that much different now. However, the European species are well-grown and the towering gums in the tall image (below) have joined while others collapsed, long since, across Barkers Creek, which runs from the north between the gardens and the caravan park and swimming pool.

It’s a romantic image, in keeping with the pictorialist style that dominated art photography of the period right up to World War 2 in Australia, defended by its “blurry eye” proponents with much friction against the modernist “third eye” school in the 1930s, especially in meetings of the Sydney Camera Circle. Taken probably in 1905, these pictures were made when pictorialism had a firm hold.

Still in original frames, their mounts obscure their inscriptions. Only the word “Copyright”, in white, appears and can be seen to have been written in the same hand on each. Darkened script (signatures?) is illegible on each.

The burnt umber outer mounts of both have the same title—Botanical Gardens Castlemaine—in a high-waisted round italic script, used also to sign “A. Verey & Co. Castlemaine” on the lower right-hand corner of the horizontal.

But Verey brothers are not the photographer: they are attributed to R. Scott. Adolphus Verey (1862–1933), who had learned photography as an apprentice in Melbourne, built his own studio (soon extended to two storeys) on the corner of Barker and Lyttleton Streets in Castlemaine in what, since 1964, has been the chemist’s but still boldly bears the sign A. Verey & Co on both frontages.

Postcards sold by Verey & Co can still be found in secondhand and antique shops in the district, and perhaps Scott’s pictures were sold as framed prints to locals. The light-hearted quality of the Verey brothers’ own work can be gauged from this earlier scene, photo-bombed by a man standing obstinately at centre, arms folded, and his son with his penny-farthing beside him, in the then 20-year old gardens in around 1884.

So who was R. Scott?

Gael Newton’s essay ‘Out of Sight’, in Shifting Focus: Colonial Australian Photography 1850–1920 offers this:

"Robert Vere Scott was born in Brisbane in 1877, the seventh of ten children of a Scottish immigrant storekeeper father and an Australian mother. Nothing is known of his early life or training other than that he was based in Port Pirie, South Australia and was working as a photographer when he married in Adelaide in 1899. Vere Scott is first listed professionally in outback Broken Hill in 1900 but signed his images in the negative rather grandly as ‘R. Vere Scott’."

The vertical panorama is a departure from Scott’s more prosaic, usually elevated, horizontal views of city streets and cityscapes such as the accompanying view of Castlemaine in the current exhibition Cloudy—a few isolated showers at our gallery.

Though based in Port Pirie, during this time Scott traveled to Castlemaine and along the south-east coast, though the dates are rubbery; photographs he made in New South Wales, South Australia and Western Australia, and later in New Zealand, are scattered across Australia’s public institutions and all bear close, estimated dates.

Though none of his negatives have survived, it is likely that these shots in Castlemaine were taken with the 1899 Kodak Panoram No. 4 camera or the No. 1 of 1900 with swiveling lens housed in flexible leather and curved film holder. The swinging lens mechanism constituted the slit-scan shutter, exposing the length of the frame progressively as it turned to cover the angle of the shot and aimed away from the film at either end of its scan.

An article in The Adelaide Register of 19 December 1907 declared that Vere Scott had “‘recently imported the largest panoramic camera that had yet been brought to the Commonwealth, and that it was designed to take pictures 24 x 9 inches”. That camera may have been the more cumbersome Kodak Cirkut of 1904; a large format bellows camera that could be converted to make panoramas by mounting it on a clockwork turntable coupled to a spool of film that unrolled past a slit at the film plane, and was capable of 360º views with a resolution breathtaking even by current digital standards. Produced until 1945, it is used by some, even today.

Panoramic views of course had been produced in Australia since the late 1840s; however, these turn-of-the-century cameras made it possible to encompass the whole view in a sweep on one piece of film, rather than laboriously piecing together panoramas from a series of separate glass plates.

Both Scott’s Castlemaine images are heavily manipulated, with selective burning in and vignetting and a sense of depth exaggerated by the wide angle. But by turning the camera on its side, Scott encourages a sense of spatial immersion, carefully organised around divisions of thirds that arrest our eyes on their transit from the depths of the water, seen probably from the bridge at the top of the gardens, through the passage of the creek into the distance, and following the wind-battered trunks into the clouded reaches of the moon. To augment the effect, Scott has painted in extra top-lit clouds in Indian ink on his negative.

Castlemaine Art Museum is fortunate in possessing a rare (possibly unique) example of Scott’s more artistic work. It is in his ‘moonlit’ style—actually an underexposed negative printed heavily to look nocturnal, as can be confirmed from the sharpness and lack of motion blur of water in both images, which would be impossible to achieve with the long exposures required under the light of the moon.

Later in 1907, Scott set up a commercial studio on the goldfields of Kalgoorlie, and produced far less romantic, but professional, pictures of horse races and other sporting events for the Kalgoorlie Western Argus and covered mining activities for a long article in The Lone Hand. His work subsequently featured among the copious photographic illustrations of journalist Edwin J. Brady’s 1918 tome Australia Unlimited, which proposed transforming the desert interior with modern technologies to support 200 million Australians. The trail fades there, as Scott left Australia for another frontier, Almeda County, California, in 1918. Though he later set up studios in Boston, nothing is preserved from his photography in the United States.

James McArdle

March 2021

A longer version of this article appears on McArdle’s blog here.

This reflection is supported by the Victorian Government through Creative Victoria’s Digitisation Roadshow program.