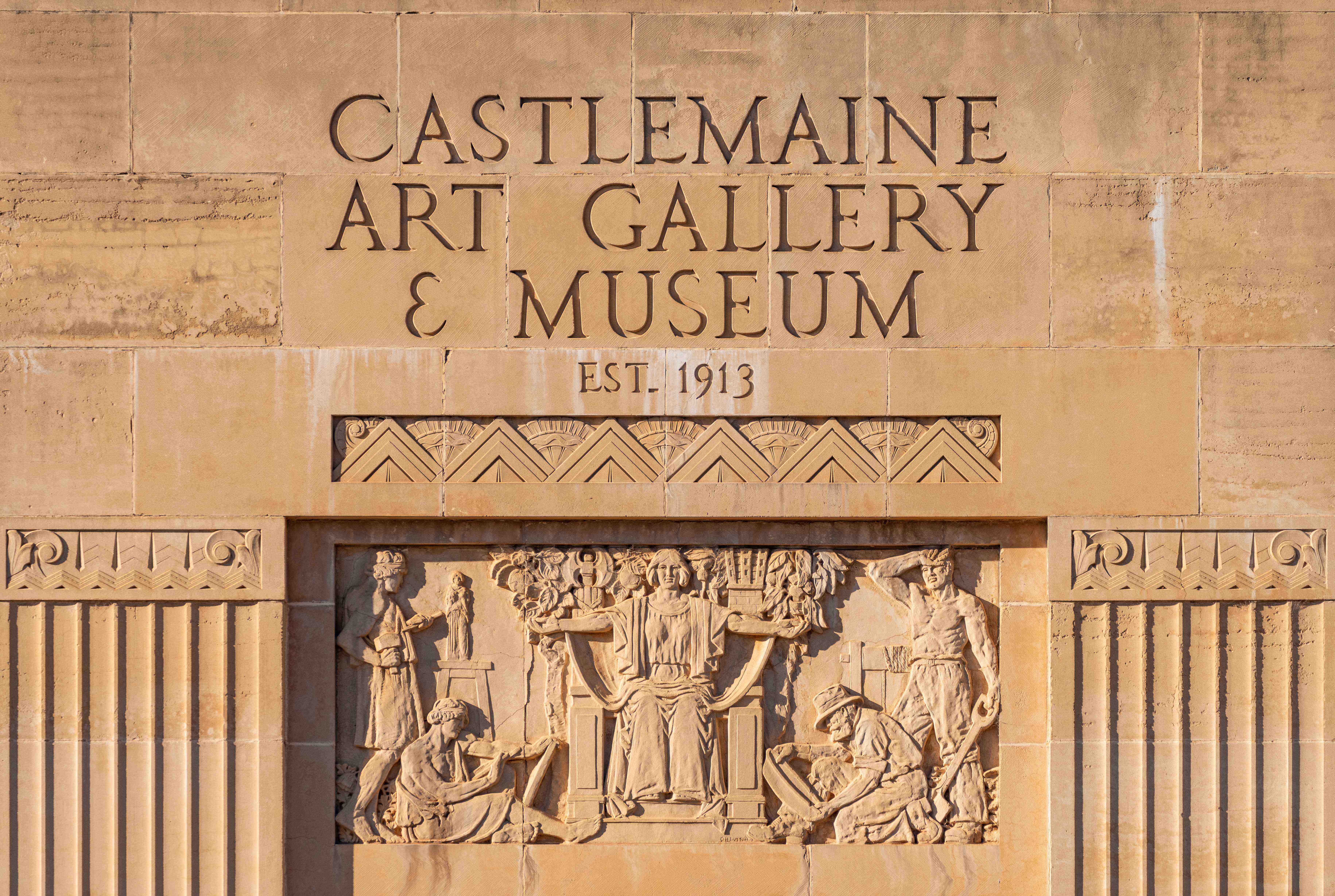

McArdle on Dutton's Bas-Relief

Architectural details have long been inspired by myth, heraldry and symbolism, dating back to the classical era. Such is the case for Orlando Dutton's bas-relief on the Museum's façade.

Here, local artist and writer James McArdle explores the history and subject of the bas-relief, accompanied by his photographs of the façade in the early morning's raking light.

James McArdle on Orlando Dutton's Bas-Relief

Orlando Henry Dutton, whose initials and surname are on the sculpture, was an Australian immigrant born in Walsall, Staffordshire, on 1 April 1894. After fighting in WW1 and contracting malaria in Malta, he followed other members of his family to South Australia in 1920, marrying there and completing four bronze reliefs that surround the obelisk of a war memorial in the town Booleroo Centre (confirmed in my query to State Library, SA) from memories of his own wartime experiences, before setting up in Melbourne.

The son of a baker, he was trained as apprentice to an architectural sculptor in Lichfield as a stone carver, and was employed on buildings in various parts of England before coming here, where he also fought in the AIF in WW2. At sixty-one on a nostalgic return to England in 1955, he revisited his beloved home town, and his early sculptural commissions, intending to settle permanently with his then 75-year-old wife Emma. Tragically she died there. He returned to Australia in 1960, and died two years later.

I have tried to discover if Percy Meldrum, architect of the 1931 CAM building, commissioned Dutton directly. Perhaps he knew of sculptures on which Dutton was working for the façade of the Manchester Unity Building at the intersection of Collins and Swanston Streets. Below is one of its duplicate sculptural groups from the facade's bas-relief, from Ken Scarlett’s Australian Sculptors (they are six stories above the street).

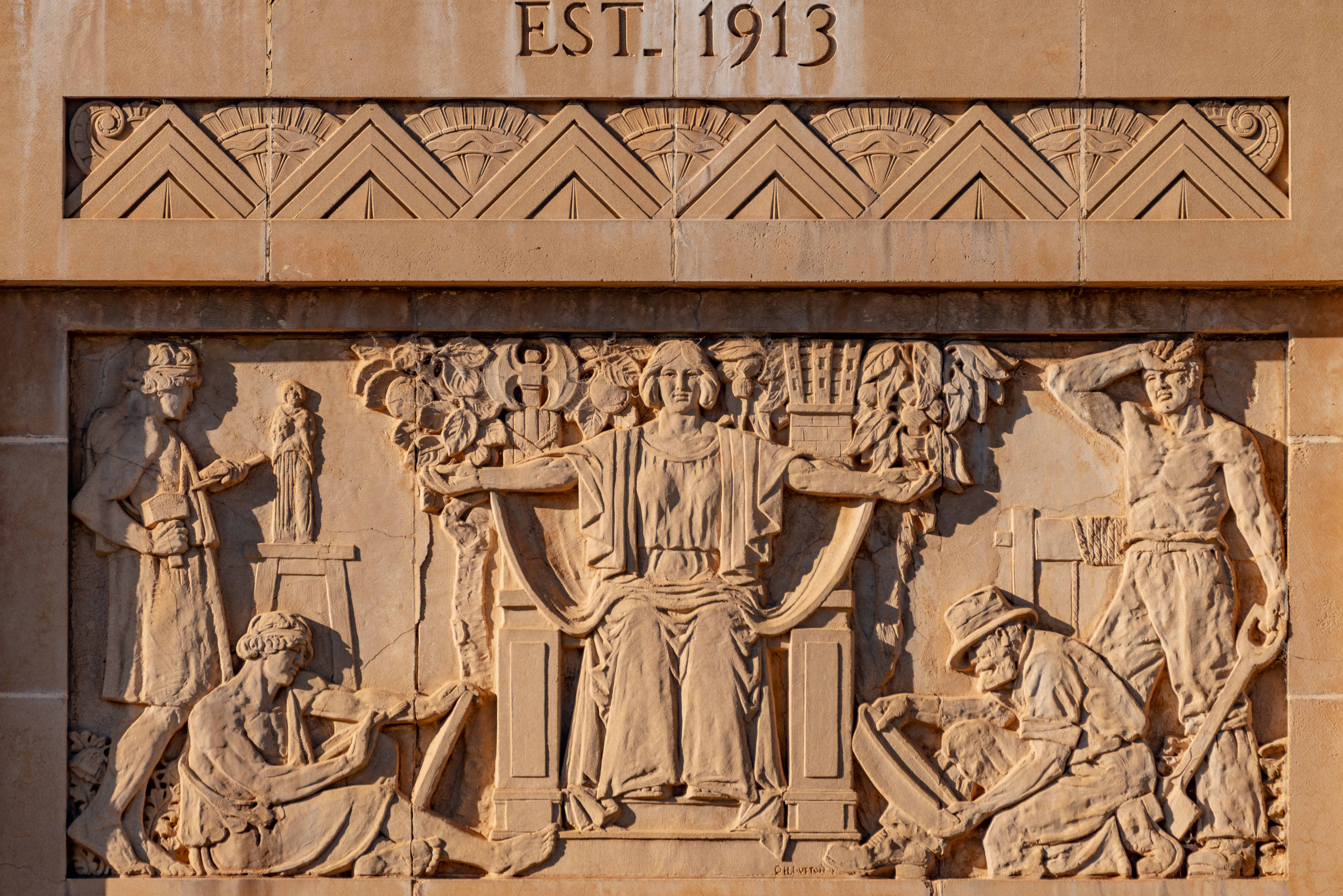

Even with the assistance of young Stanley Hammond over 1930-32, Dutton was under pressure to complete these and other commissions at the same time. His solution was ingenious; both the CAM bas-relief and the Manchester Unity sculptures are cast from moulds… expedient in the case of the Melbourne commission given the need for identical sets of figures (Faith, Hope and Charity) above each entrance on the corner block.

For that, he used high-fired terracotta cast in pieces and assembled for installation. For CAM, since it had to be transported from his Melbourne studio, he cast the bas-relief in artificial stone. The process is evident in the way none of the shallow figures is undercut, so that it could be easily extracted in three pieces from the negative mould, itself cast in plaster from a clay original. That is why no chisel marks are visible, and you can see the incisions into wet clay that form spare line work… it is modelled additively, not sculpted 'subtractively' in the traditional sense.

That technique is echoed in the planters on the terrace by sculptor and textile artist Michael O’Connell, also from England, who made them and his house ‘Barbizon' in (Clarice Beckett’s) Beaumaris in cast concrete. Their panels in warm artificial stone depict local native animals.

The subject of Dutton's bas-relief is understood from its symbolism. The identity of the central female figure is conveyed by the fact that her throne bears on her left a ‘mural crown’ which looks like it is made of brick or stone blocks. The crown descends from that legendary golden band or halo bestowed on the Roman soldier who was first to breach the walls of a city or fortress besieged by his army (though earlier mural crowns appear on heads in Greek sculptures too).

It was taken up in medieval heraldry, and appears on coats of arms of many countries, including that of Malta where Dutton fought, and is the symbol of the guardian deity of nations, states or cities. So the woman at the centre of CAM's building façade is the goddess of Castlemaine.

To reinforce her power, at her right appears the fasces carried by the attendants of any Roman authority figure, be they magistrates, senators, or emperors. It is a bundle of birch rods - truncheons in effect - and when carried beyond Rome’s walls, they were bound around a battle-axe - in this case double-headed, to be used to punish any who would defy Roman law. Originally a literal symbol of punitive ‘fascist’ authority, here, they may attach to another legend, that of Aesop’s tale of a despairing father whose sons were constantly fighting. For their edification he presented each with sticks tied in a bundle which he challenged them to break. None could. He then untied the bundle and gave each son one of the sticks, again inviting them to break them, which they did easily. “United," he said, "you are strong. On your own, you can be defeated. Agree, look out for each other, and you may thrive.” That may be the intention here… it was a dedicated group of women who united to realise the building of CAM.

The figure we know is Castlemaine herself, gestures broadly. On one side, she takes the gold dug out by the miners depicted on our right, labouring in the mud of Forest Creek with shovel and pan, and uses it to build Castlemaine. On the other she gives of this wealth to artists; a painter, and a sculptor who perhaps carves a version of herself with his mallet and chisel.

The miners’ windlass and the sculptor’s plinth; and the mound of miner’s clay and the leaves of acanthus at the artist’s feet; in the corners these forms bracket the strict symmetry, like that of the whole gallery façade. Those leaves emerge from another Roman tale told by Vitruvius in which Greek architect Callimachus saw on the grave of a little girl that her nurse had set a basket of her favourite toys and placed a slate upon it to protect it. Acanthus around the grave had grown through the basket, thus inspiring the ornate Corinthian capital.

Stout trunks growing beside the throne of the goddess Castlemaine sprout more leaves above her head; flowering gum to the right, and over the artists, laurel, the symbol of triumph worn by champion athletes and poets laureate, and of the women whose vision is realised in this building.

As you walk through the iron porch gates to enter the Art Museum you pass under another relief, a scallop shell in stone placed directly above the glass doors. In heraldry it is the badge of those who had been on the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela, and here it belongs to pilgrims of art, the visitors to CAM.