Felstead on Fairweather

Local artist Ken Felstead reflects on three wonderful works in our collection by Ian Fairweather. Weaving together aspects of Fairweather’s biography, Felstead introduces some of the philosophical and artistic influences on Fairweather’s work. Felstead will be known to many visitors as a finalist in the last two Len Fox Painting Award exhibitions at CAM.

Felstead on Fairweather

Ian Fairweather, born in Scotland 29 September 1891, lived an austere, often nomadic life, and was intensely private, reclusive and generally not influenced by social norms. After time as a prisoner of war in World War I, he studied painting at the Slade Art School in London, and lived and worked extensively in China and throughout Asia before landing in Australia in 1934, where his work was immediately valued by the likes of Melbourne artists George Bell, Jock Frater and Arnold Shore, and the art entrepreneur Gino Nibbi.

Cynthia Reed’s gallery exhibited his work almost immediately. He was later successfully shown in Sydney, London, Pittsburgh and the National Gallery of Victoria. Fairweather made news headlines in 1952, when he spent 16 perilous days at sea on a homemade raft in an attempt to reach Timor. After an enforced sojourn in England, he returned to Australia and eventually built two bark huts on Bribie Island, off Moreton Bay, Queensland, one of which was used for living, the other for painting. He died on 25 May 1974.

Fairweather’s intellectual outlook was shaped by Chinese culture and Zen Buddhism, and his art was informed by a complex amalgam of influences from Turner, Cézanne, Cubism, Chinese calligraphy and Aboriginal painting.

When the philosopher Martin Heidegger speaks of representation in art, he emphasises its inherent notion of re-presentation. Or as Picasso was known to say: “We all know that Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realise the truth.” That “truth”, however, is the artist’s understanding of the truth. Artworks are objects within themselves which are derived from the artist’s outlook on life, their preoccupations, and the skills through which they convey or re-present the images and ideas which inspire them. The resulting artworks provide the viewer with the means of sharing the artist’s understanding of the world. Importantly, Fairweather became progressively less interested in the depiction of a scene and more interested in using the scene or idea to express his response to it

The earlier simpler characters in Chinese writing developed out of pictograms. These are images that were simplified and formalised to the point of near abstraction. Fairweather discovered in his study of Chinese calligraphy that the discipline of the use of brush in writing these characters was founded on an ethical imperative to provide an aesthetically pleasing and therefore respectful expression of what was being represented. His Untitled Landscape (top image) is an example of that presentation of a simplified summary of the scene before him. It operates as an unapologetic play of paint articulated by lines, some of which are over-painted almost to oblivion. The whiter segments of the dominating light-coloured lines are suggestive of hills, and—in the European tradition—are placed in the frame at the point of the square in the Golden Mean; the muted subtlety of colouring in its dark earth brown and the almost white overlay outlines, all of which are modified in varying degrees by a delicate over-painting of pink, are reflective of his absorbing some of the traditions of Aboriginal picture-making.

Fairweather—in an oft-quoted statement—claimed that “Painting to me is something of a tightrope act; it is between representation and the other thing—whatever that is.” This is aptly demonstrated in the deceptively casual and freely expressed Glass House Mountains (above). While the contrasting cooler blues in the upper half of the picture keep our eye centred, and the horizontal lines in the lower half maintain stability, the wilder, freer gestures evoke the transient elusiveness and apparent chaos of nature. The resulting transparency of the mountains indicated by the restless sweeping white lines imposed roughly in the vicinity of the previous, darker iterations of the mountains is a strategy to the same end, and is a synthesis of both the Aboriginal uses of X-ray type imagery and the Cubist notion of multipoint of view: not all aspects of the subject are presented as a fixed image in place and coinciding in time.

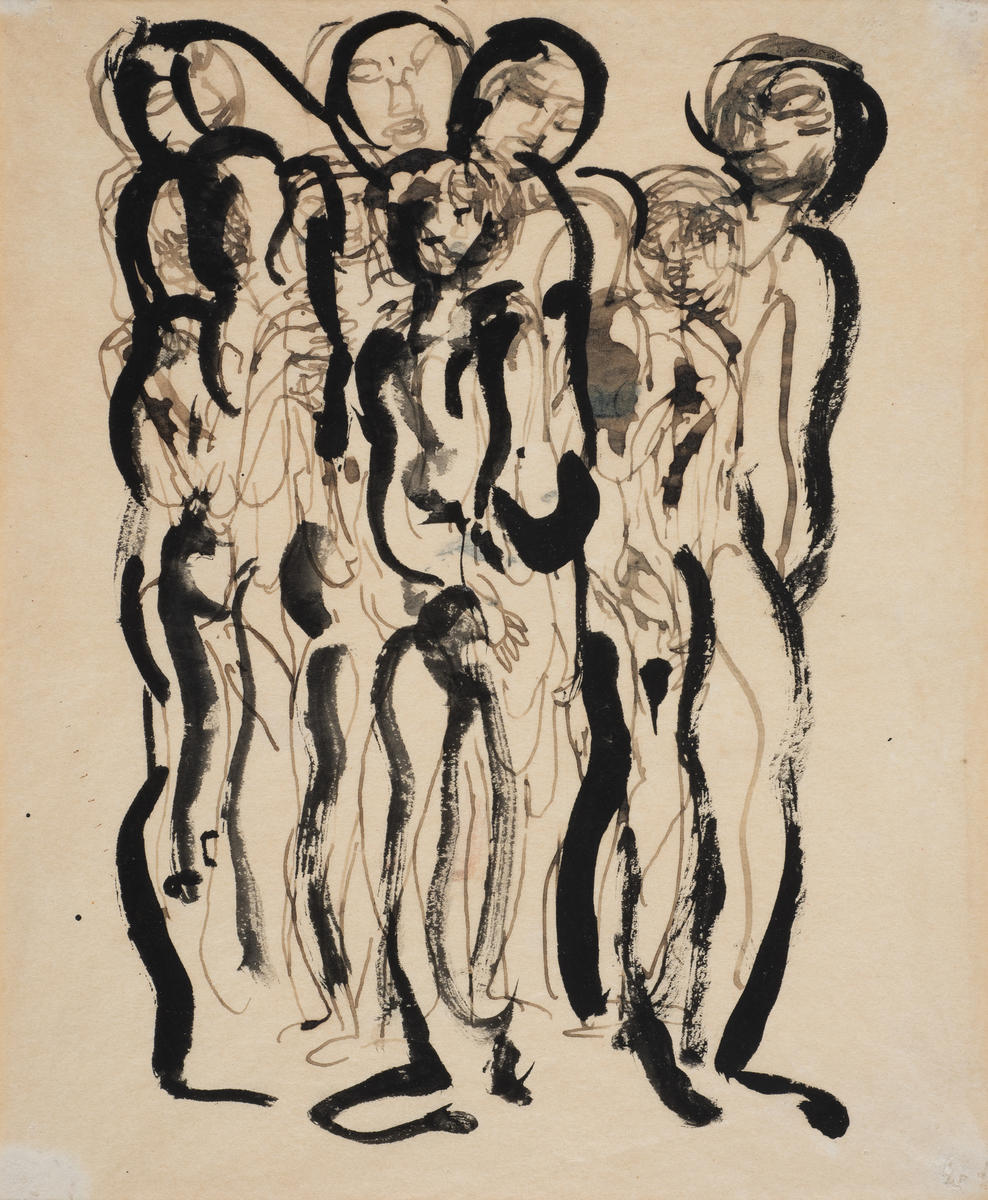

The same can be said of the drawing of a group of figures (above). This is not a portrait of a specific group, but rather an impression of the vibrancy of a group of young people out inhabiting their world. Initial thin pen lines capture ideas of their individual moving outlines as they interact and move as a group, but then the individuals are subjugated, confined even, to their place within the group, as Fairweather imposes a vertical rhythmic simplification of that energy with the use of thicker, heavier brush strokes which owe much to his study of Chinese calligraphy.

These three small pieces, then, through a synthesis of his life experiences and interests into a form of individual expression, provide some insight into Fairweather’s world.

Kenneth Felstead

June 2020