Conway on Rees

A great joy of CAM's Reflection series has been the response we've received from our extended community, the many people who have contacted us to offer follow-up thoughts, to provide further recollections, to add details about collection items. Kerry Conway is one such reader, inspired to share her thoughts on a Lloyd Rees image. Here, she explains why his work resonates so strongly with her.

Conway on Rees

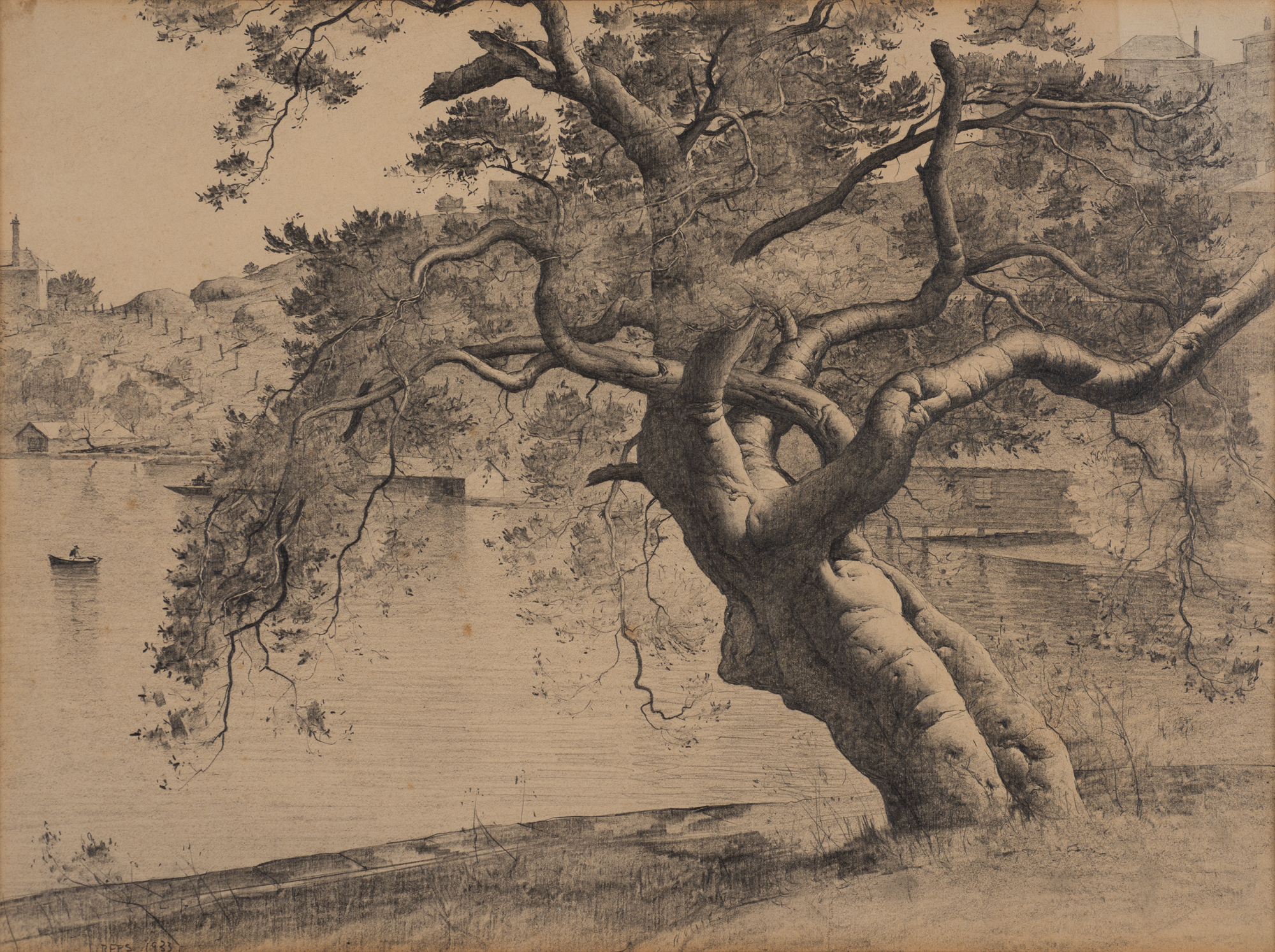

Lloyd Rees’s drawings are masterful. He has the capacity to distil the spirit held in nature, in this case, in a Moreton Bay fig tree; a gnarled, broad sinuous trunk; a tree which commands you look at it. I take in its trunk—the contorted, thick-set trunk which from some angles reflects a muscular human form—then look along the arching branches, to the filigree smaller stems, to the miscellany of leaves. And then to look up into the wide and protective canopy, and consider how long this remarkable tree has lived, its roots still deep in the soil. I wonder at how this fig has been here for many decades, enduring hot Australian summers, cold winters, wet seasons, and drought. This is Lloyd Rees’s achievement, using a pencil and paper.

“As with practically all my work there must be a motivation, a central theme, a moment of vision or creativity,” Rees said. Also, “The miraculous is around us all the time.” The recognition that landscape art has a spiritual element has been present from its beginnings in East Asian art, in the drawings of Taoism, but in the West, this only became explicit with Romanticism, in the 17th century.

Lloyd Rees was born in Sydney in 1895 and died in 1988, after a lifetime of almost continuous painting, drawing and etching. Although he painted most of his work in New South Wales, he also painted in Italy, France and England. He admired Bellini, Corot and Turner, among others. He didn’t belong to any art movements.

Rees became interested in painting and drawing at a very young age. He remembered doing watercolour paintings inside the lids of his mother’s hat boxes; they were very big, and the lids were very good to paint on, he said. And drawing friezes of trains along the verandah walls.

A breakthrough discovery was that drawing on fine paper with a pencil sharpened to a fine point was capable of achieving results of an almost ink-like density, while also permitting the soft nuances of shading, passing through every degree between luminous white and almost jet black.

Christopher Allen, writing about Rees’s achievements, noted that drawing is “a sophisticated intellectual process” (The Australian, 12 March 2016). He says Rees’s sense of the formal tension between verticals and horizontals, between close and far, or between nature and architecture is as precisely calibrated as musical composition.

Rees is one of the most admired artists in Australia.

The beauty and the power in his drawing of the Moreton Bay fig tree simply expresses his virtuosity. His drawing demonstrates some of the mystery and wonder of the natural world, and how precious it is.

Kerry Conway

December 2020

Lloyd Rees’s drawings are masterful. He has the capacity to distil the spirit held in nature, in this case, in a Moreton Bay fig tree; a gnarled, broad sinuous trunk; a tree which commands you look at it. I take in its trunk—the contorted, thick-set trunk which from some angles reflects a muscular human form—then look along the arching branches, to the filigree smaller stems, to the miscellany of leaves. And then to look up into the wide and protective canopy, and consider how long this remarkable tree has lived, its roots still deep in the soil. I wonder at how this fig has been here for many decades, enduring hot Australian summers, cold winters, wet seasons, and drought. This is Lloyd Rees’s achievement, using a pencil and paper.

“As with practically all my work there must be a motivation, a central theme, a moment of vision or creativity,” Rees said. Also, “The miraculous is around us all the time.” The recognition that landscape art has a spiritual element has been present from its beginnings in East Asian art, in the drawings of Taoism, but in the West, this only became explicit with Romanticism, in the 17th century.

Lloyd Rees was born in Sydney in 1895 and died in 1988, after a lifetime of almost continuous painting, drawing and etching. Although he painted most of his work in New South Wales, he also painted in Italy, France and England. He admired Bellini, Corot and Turner, among others. He didn’t belong to any art movements.

Rees became interested in painting and drawing at a very young age. He remembered doing watercolour paintings inside the lids of his mother’s hat boxes; they were very big, and the lids were very good to paint on, he said. And drawing friezes of trains along the verandah walls.

A breakthrough discovery was that drawing on fine paper with a pencil sharpened to a fine point was capable of achieving results of an almost ink-like density, while also permitting the soft nuances of shading, passing through every degree between luminous white and almost jet black.

Christopher Allen, writing about Rees’s achievements, noted that drawing is “a sophisticated intellectual process” (The Australian, 12 March 2016). He says Rees’s sense of the formal tension between verticals and horizontals, between close and far, or between nature and architecture is as precisely calibrated as musical composition.

Rees is one of the most admired artists in Australia.

The beauty and the power in his drawing of the Moreton Bay fig tree simply expresses his virtuosity. His drawing demonstrates some of the mystery and wonder of the natural world, and how precious it is.

Kerry Conway

December 2020

Lloyd Rees’s drawings are masterful. He has the capacity to distil the spirit held in nature, in this case, in a Moreton Bay fig tree; a gnarled, broad sinuous trunk; a tree which commands you look at it. I take in its trunk—the contorted, thick-set trunk which from some angles reflects a muscular human form—then look along the arching branches, to the filigree smaller stems, to the miscellany of leaves. And then to look up into the wide and protective canopy, and consider how long this remarkable tree has lived, its roots still deep in the soil. I wonder at how this fig has been here for many decades, enduring hot Australian summers, cold winters, wet seasons, and drought. This is Lloyd Rees’s achievement, using a pencil and paper.

“As with practically all my work there must be a motivation, a central theme, a moment of vision or creativity,” Rees said. Also, “The miraculous is around us all the time.” The recognition that landscape art has a spiritual element has been present from its beginnings in East Asian art, in the drawings of Taoism, but in the West, this only became explicit with Romanticism, in the 17th century.

Lloyd Rees was born in Sydney in 1895 and died in 1988, after a lifetime of almost continuous painting, drawing and etching. Although he painted most of his work in New South Wales, he also painted in Italy, France and England. He admired Bellini, Corot and Turner, among others. He didn’t belong to any art movements.

Rees became interested in painting and drawing at a very young age. He remembered doing watercolour paintings inside the lids of his mother’s hat boxes; they were very big, and the lids were very good to paint on, he said. And drawing friezes of trains along the verandah walls.

A breakthrough discovery was that drawing on fine paper with a pencil sharpened to a fine point was capable of achieving results of an almost ink-like density, while also permitting the soft nuances of shading, passing through every degree between luminous white and almost jet black.

Christopher Allen, writing about Rees’s achievements, noted that drawing is “a sophisticated intellectual process” (The Australian, 12 March 2016). He says Rees’s sense of the formal tension between verticals and horizontals, between close and far, or between nature and architecture is as precisely calibrated as musical composition.

Rees is one of the most admired artists in Australia.

The beauty and the power in his drawing of the Moreton Bay fig tree simply expresses his virtuosity. His drawing demonstrates some of the mystery and wonder of the natural world, and how precious it is.

Kerry Conway

December 2020

Lloyd Rees’s drawings are masterful. He has the capacity to distil the spirit held in nature, in this case, in a Moreton Bay fig tree; a gnarled, broad sinuous trunk; a tree which commands you look at it. I take in its trunk—the contorted, thick-set trunk which from some angles reflects a muscular human form—then look along the arching branches, to the filigree smaller stems, to the miscellany of leaves. And then to look up into the wide and protective canopy, and consider how long this remarkable tree has lived, its roots still deep in the soil. I wonder at how this fig has been here for many decades, enduring hot Australian summers, cold winters, wet seasons, and drought. This is Lloyd Rees’s achievement, using a pencil and paper.

“As with practically all my work there must be a motivation, a central theme, a moment of vision or creativity,” Rees said. Also, “The miraculous is around us all the time.” The recognition that landscape art has a spiritual element has been present from its beginnings in East Asian art, in the drawings of Taoism, but in the West, this only became explicit with Romanticism, in the 17th century.

Lloyd Rees was born in Sydney in 1895 and died in 1988, after a lifetime of almost continuous painting, drawing and etching. Although he painted most of his work in New South Wales, he also painted in Italy, France and England. He admired Bellini, Corot and Turner, among others. He didn’t belong to any art movements.

Rees became interested in painting and drawing at a very young age. He remembered doing watercolour paintings inside the lids of his mother’s hat boxes; they were very big, and the lids were very good to paint on, he said. And drawing friezes of trains along the verandah walls.

A breakthrough discovery was that drawing on fine paper with a pencil sharpened to a fine point was capable of achieving results of an almost ink-like density, while also permitting the soft nuances of shading, passing through every degree between luminous white and almost jet black.

Christopher Allen, writing about Rees’s achievements, noted that drawing is “a sophisticated intellectual process” (The Australian, 12 March 2016). He says Rees’s sense of the formal tension between verticals and horizontals, between close and far, or between nature and architecture is as precisely calibrated as musical composition.

Rees is one of the most admired artists in Australia.

The beauty and the power in his drawing of the Moreton Bay fig tree simply expresses his virtuosity. His drawing demonstrates some of the mystery and wonder of the natural world, and how precious it is.

Kerry Conway

December 2020

Lloyd Rees’s drawings are masterful. He has the capacity to distil the spirit held in nature, in this case, in a Moreton Bay fig tree; a gnarled, broad sinuous trunk; a tree which commands you look at it. I take in its trunk—the contorted, thick-set trunk which from some angles reflects a muscular human form—then look along the arching branches, to the filigree smaller stems, to the miscellany of leaves. And then to look up into the wide and protective canopy, and consider how long this remarkable tree has lived, its roots still deep in the soil. I wonder at how this fig has been here for many decades, enduring hot Australian summers, cold winters, wet seasons, and drought. This is Lloyd Rees’s achievement, using a pencil and paper.

“As with practically all my work there must be a motivation, a central theme, a moment of vision or creativity,” Rees said. Also, “The miraculous is around us all the time.” The recognition that landscape art has a spiritual element has been present from its beginnings in East Asian art, in the drawings of Taoism, but in the West, this only became explicit with Romanticism, in the 17th century.

Lloyd Rees was born in Sydney in 1895 and died in 1988, after a lifetime of almost continuous painting, drawing and etching. Although he painted most of his work in New South Wales, he also painted in Italy, France and England. He admired Bellini, Corot and Turner, among others. He didn’t belong to any art movements.

Rees became interested in painting and drawing at a very young age. He remembered doing watercolour paintings inside the lids of his mother’s hat boxes; they were very big, and the lids were very good to paint on, he said. And drawing friezes of trains along the verandah walls.

A breakthrough discovery was that drawing on fine paper with a pencil sharpened to a fine point was capable of achieving results of an almost ink-like density, while also permitting the soft nuances of shading, passing through every degree between luminous white and almost jet black.

Christopher Allen, writing about Rees’s achievements, noted that drawing is “a sophisticated intellectual process” (The Australian, 12 March 2016). He says Rees’s sense of the formal tension between verticals and horizontals, between close and far, or between nature and architecture is as precisely calibrated as musical composition.

Rees is one of the most admired artists in Australia.

The beauty and the power in his drawing of the Moreton Bay fig tree simply expresses his virtuosity. His drawing demonstrates some of the mystery and wonder of the natural world, and how precious it is.

Kerry Conway

December 2020